The question of Ascher’s relationship to his Jewish origins is complex, and difficult to parse. Yet, perhaps less by choice than by circumstance, that Ascher had Jewish roots became a defining characteristic of his life story due to Nazi persecution.

Ascher’s family left the Jewish community officially in 1899; though his father, Hugo, and mother, Minna Luise, never joined the Protestant church, Ascher and his sisters were baptized in 1901. Ascher’s sisters both married non-Jews, and the family trod the path of many wealthy German-born Jews before them, converting to Christianity for safety, social assimilation, a shift in religious feeling, or perhaps a combination of the above. The precise causes of German Jewish conversions in the late-nineteenth and early-20th centuries were varied, and Ascher’s family’s motivations may remain unknown.

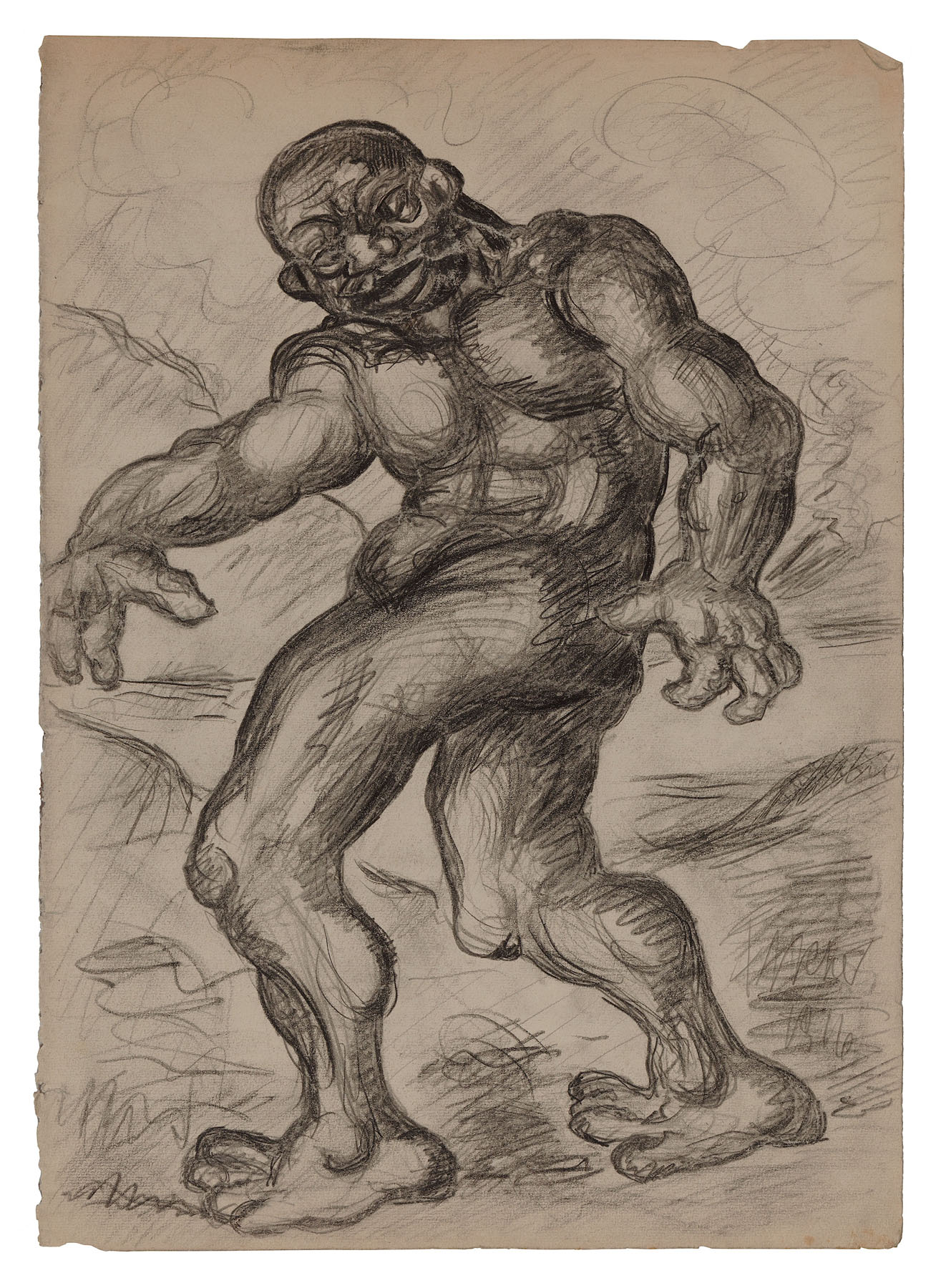

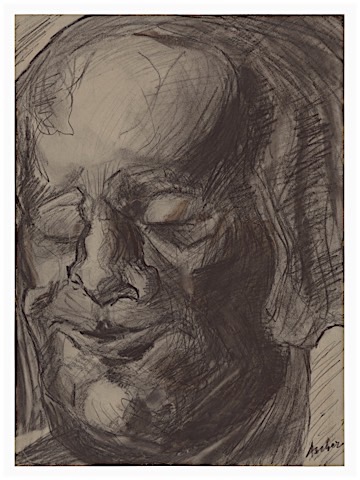

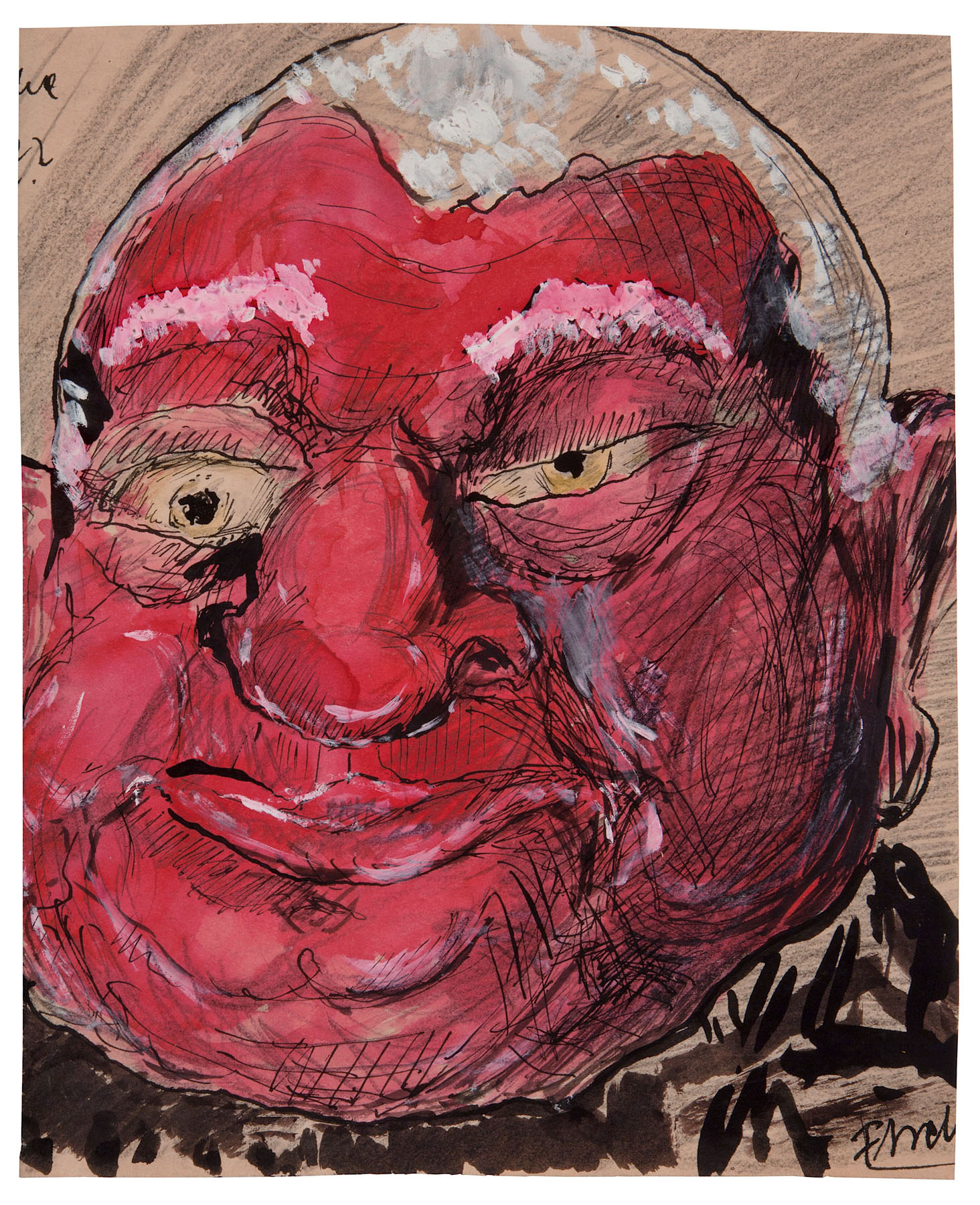

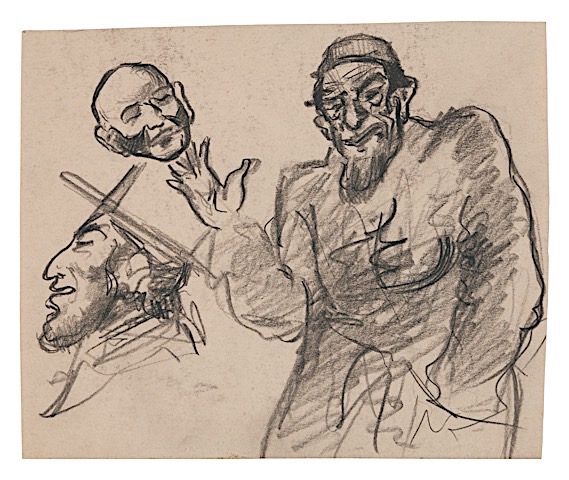

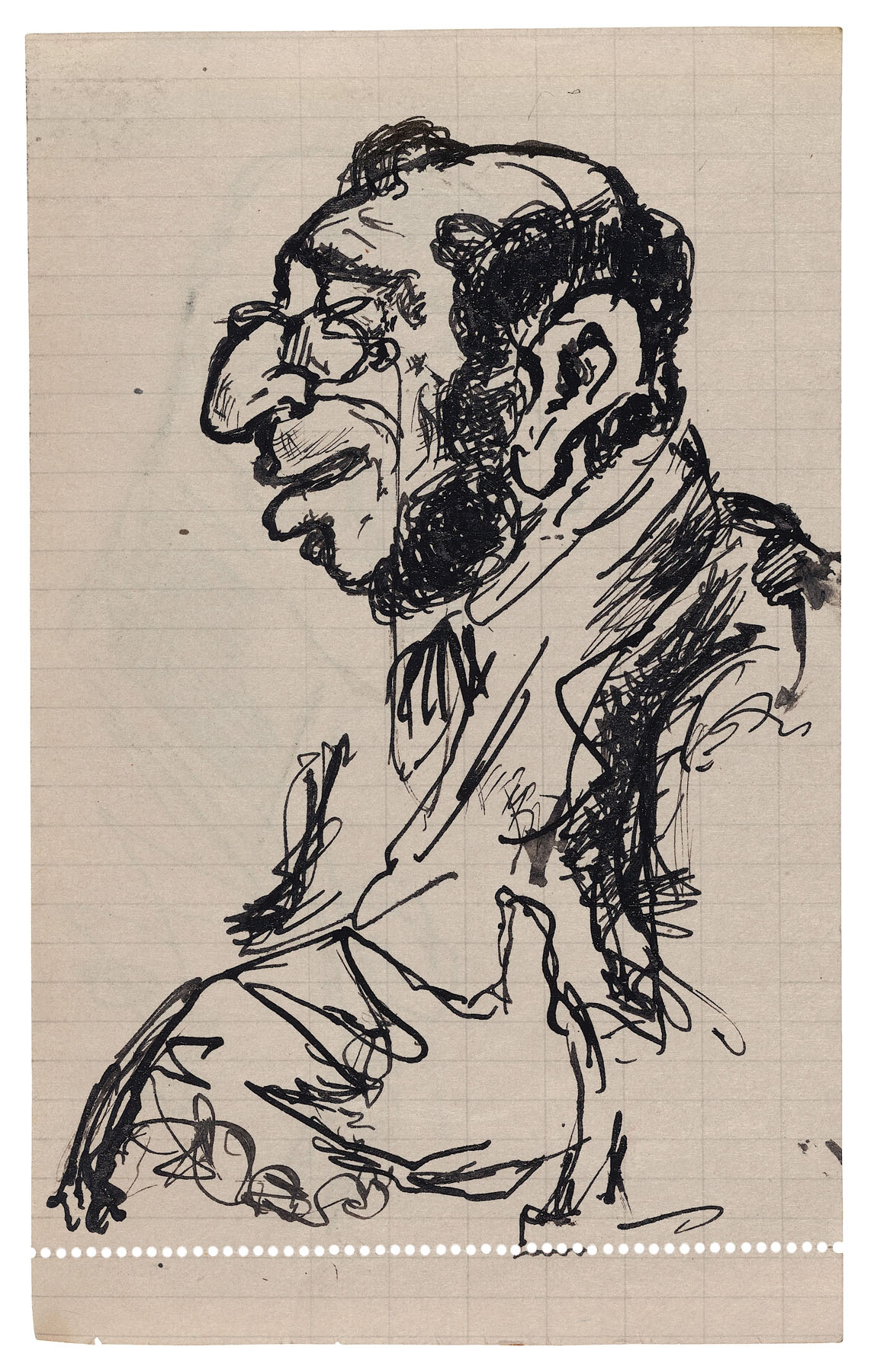

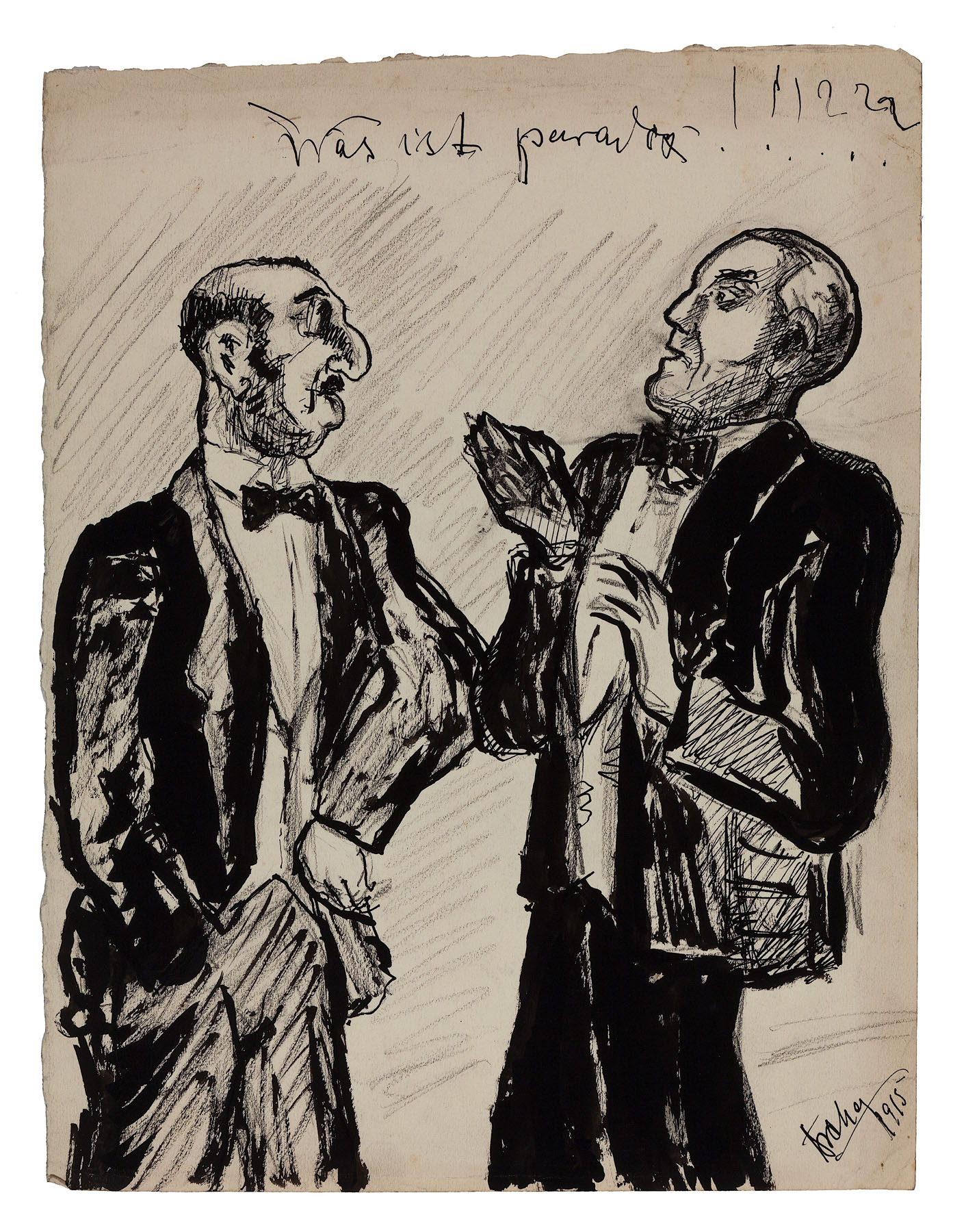

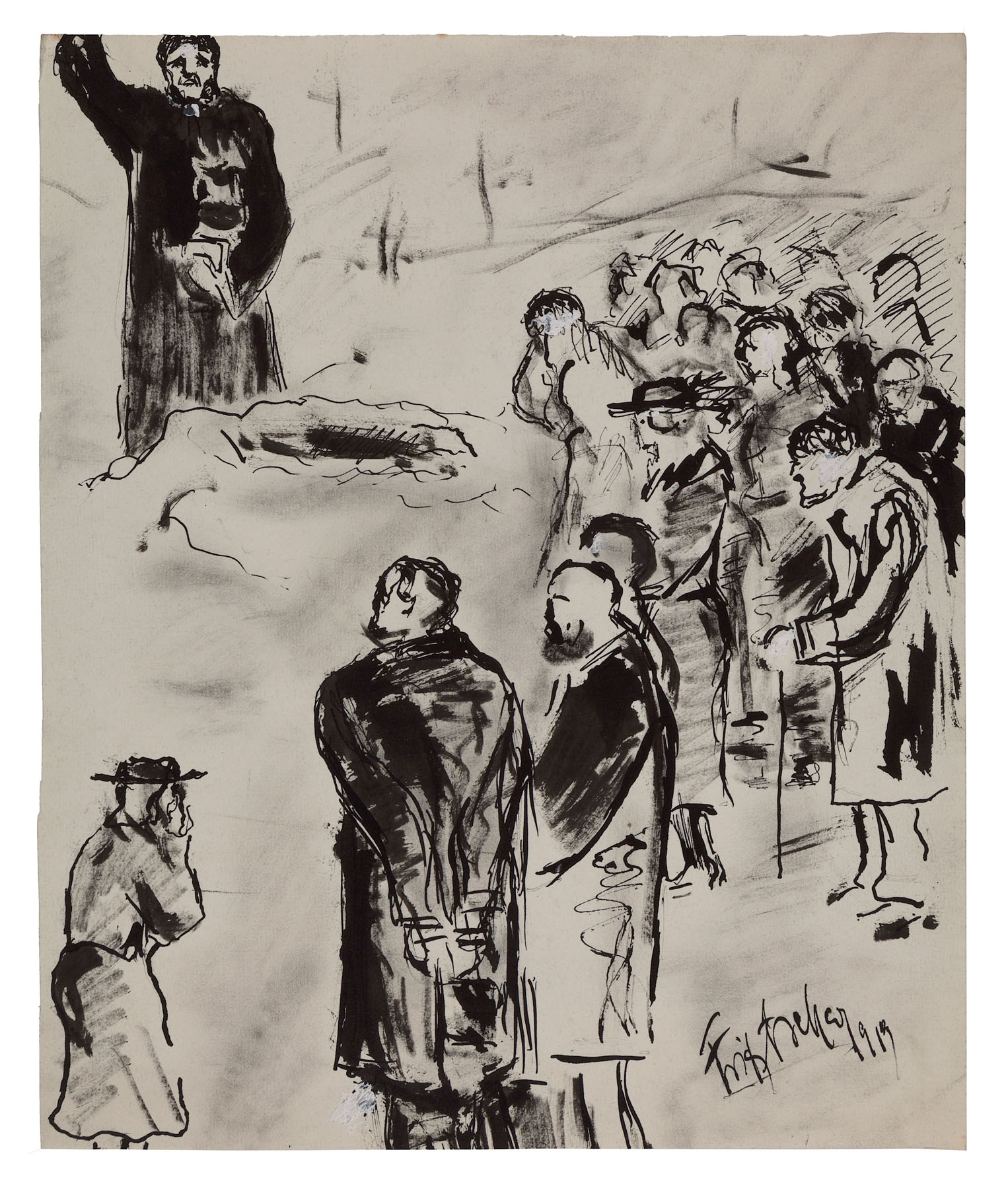

However, Judaism and aspects of Ascher’s Jewish roots appear in various forms throughout his work. From Burial (1919) to his studies of “Jewish” typologies to Golgotha (1915) to The Golem (1916), facets of Jewish mythology, imagery, and make apparent life within a Berlin community defined by a wide range of Jewish practice–from Jewish converts to Christianity to religious, Eastern European Jewish refugees and immigrants.

That some aspect of Ascher’s Jewish identity remained a part of his outlook or his work is not contradicted by those works which explicitly deal with Christological themes. Just as peers such as Marc Chagall embraced Christian iconography as a tool to explore universal themes or a vehicle through which to comment on contemporary events, so, too, should Ascher’s interest in infusing his works with Christian as well as Jewish subjects and topics not be viewed as proof that he had embraced or abandoned one faith over another.

It was, however, Ascher’s connection to Judaism by birth that most profoundly shaped his life and career trajectory once the Nazis came to power. After 1933, Ascher was forced into hiding from the Nazis and was briefly imprisoned in Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp. He was released in 1938, but then shortly thereafter arrested and jailed in Potsdam. In 1939, Ascher’s connections garnered him a release, but a plan to emigrate to Shanghai did not succeed. By 1941, the SS had repossessed Ascher’s family home, and in 1943, Ascher’s family assets were seized. From June 1942 until the conclusion of the war three years later, Ascher went into hiding in a family friend’s basement—a Grunewald neighborhood where he was surrounded by homes newly occupied by high-ranking Nazi officials. This was a life of constant fear, confinement, loneliness, isolation, and hunger, and the trauma of the experience was one Ascher carried with him for the remainder of his days. Nazi persecution robbed Ascher of the life and distinguished artistic career he was on the cusp of achieving, and left lasting psychological scars that perhaps can be identified through examination of his work.

Whether or not Ascher truly self-identified as a Jew during his adult life will forever remain open to debate. In some senses, not knowing whether or not he himself embraced his Jewish heritage fully, despite his conversion, makes the concept of labeling him “Jewish” problematic, as if adopting the designation of his Nazi tormenters who saw him as Jewish, regardless of his conversion. The fact remains, however, that Ascher’s Jewishness—whether personally embraced or disregarded—became a source of inspiration for his major artistic works and dramatically impacted his career as the cause of his persecution and forced hiding under National Socialism. By choice as much as by circumstance, Judaism thus circumscribed Ascher’s life, work, and artistic production.

DigiFAS Quick Clips

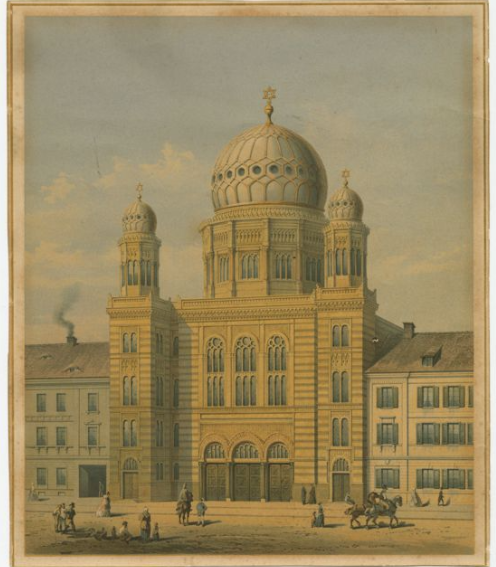

Fritz Ascher and Jewish Berlin

Der Golem, 1916

Studies for Der Golem as well as selections from Fritz Ascher’s studies of “Jewish Types”

The Golem: How He Came Into the World, 1920 film

Directed, written, and starring Paul Wegener; also directed by Carl Boese and written by Henrik Galeen

This silent film is the third in Wegener’s Der Golem trilogy, the first of which debuted in 1915.

Scholarly Articles

Explore Further