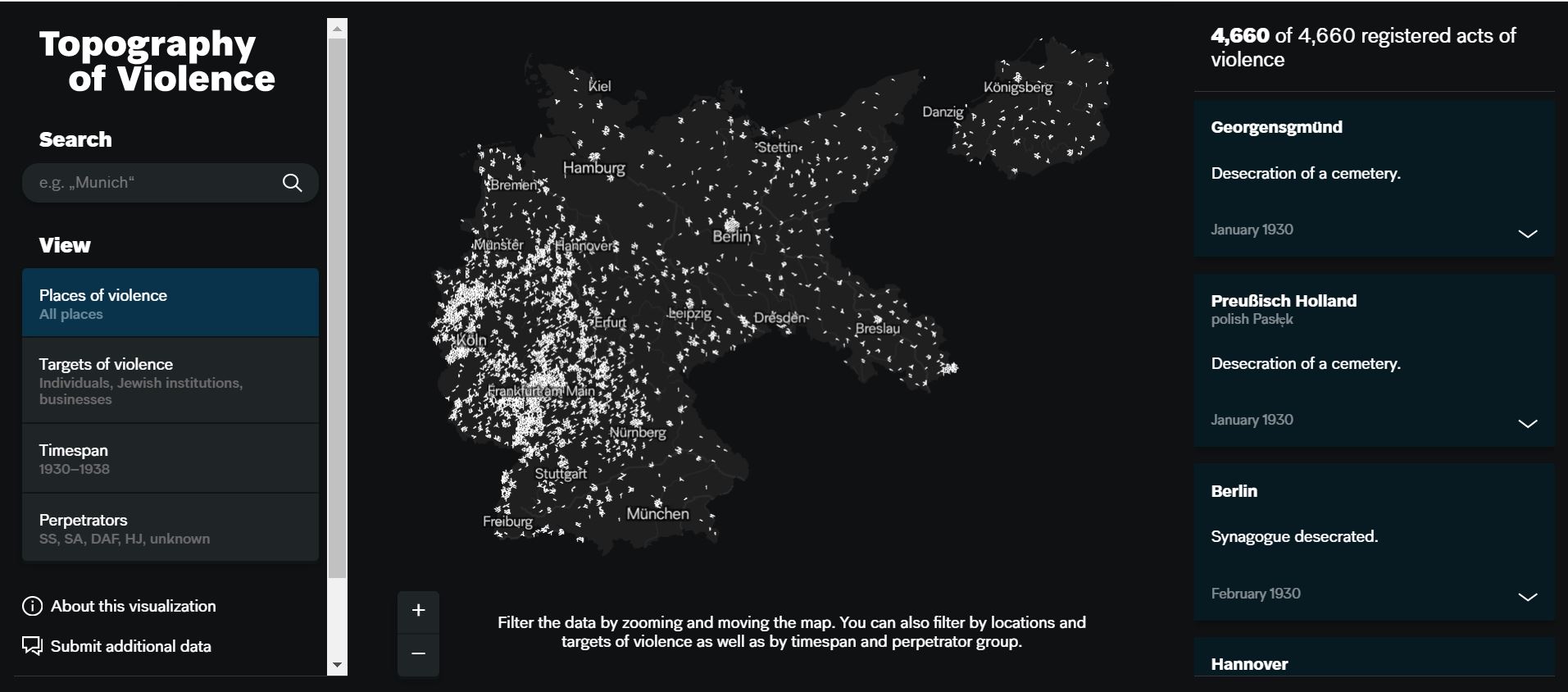

Fritz Ascher’s adult life and career were, in many ways, defined by a series of traumatic events. Though his parents converted Ascher and his sisters to Protestantism, his Jewish roots resulted in Ascher’s persecution under National Socialism. After the Nazi ascension to power in Berlin, Ascher could no longer work or sell his art, frequently changed residences in order to elude capture, and confronted the death, on his birthday, of his mother, Minna Luise.

Ascher was deported to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp during the November pogroms in 1938, released with the support of a family friend, and then re-arrested in Potsdam. After his second release from captivity, Ascher attempted to flee Germany for Shanghai, but was prevented from doing so. His family home was taken over by Nazi officials, with any hope of income from the property completely eliminated, and his assets were formally seized by the Nazi party in 1943. After a variety of maladies caused by his internment resulted in a hospital stay, Ascher was tipped off that his next deportation order was imminent. He turned to a friend’s mother, who hid him from June 1942 in the basement of her Grunewald home. Isolated, unable to paint, confined to the basement and locked in the tiny space of a potato cellar during air raids, Ascher lived out the remainder of the war years in fear, surrounded by the high-ranking Nazi officials who lived or who had repurposed the neighboring Grunewald homes.

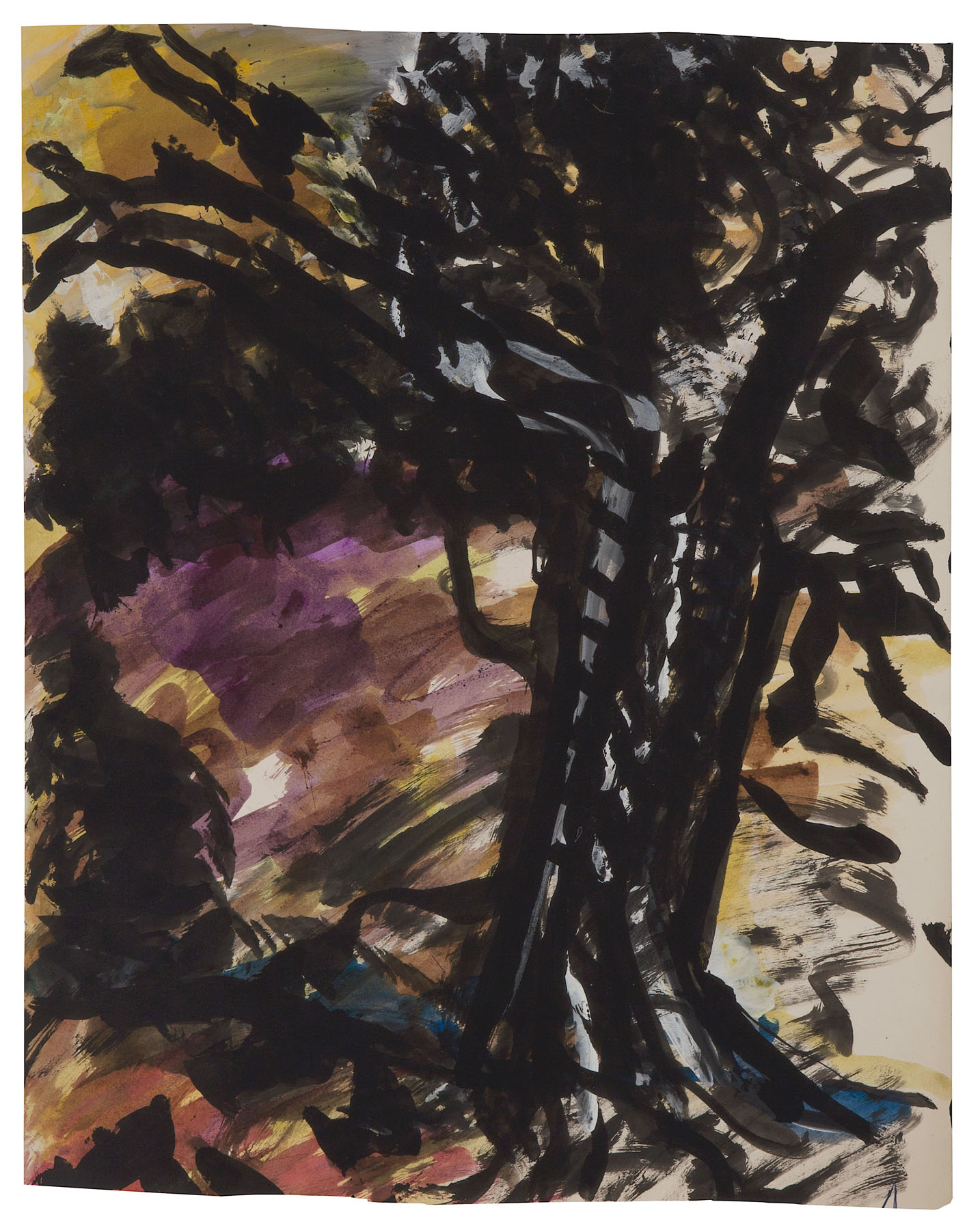

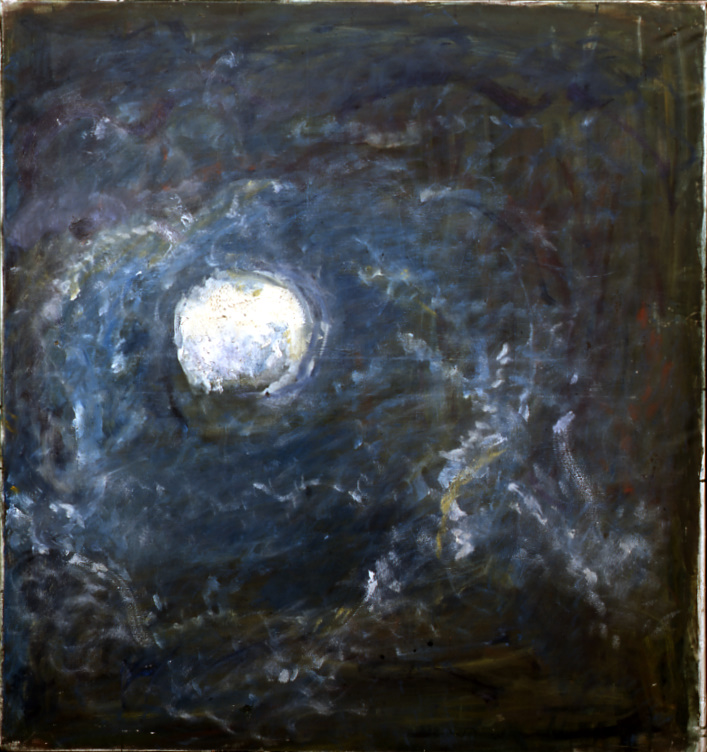

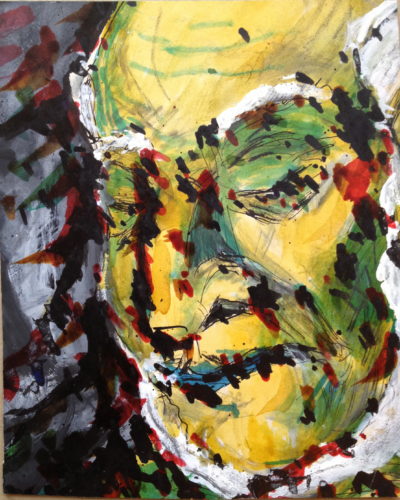

Following the Shoah, Ascher’s life couldn’t return to what it was prior to Nazi persecution. He moved in with Martha Grassman, his mother’s friend who had sheltered him throughout the later war years. He resumed painting, and even exhibited, yet turned down an offer to teach from the Art Academy of Berlin, citing social anxiety. Though he had a girlfriend or female companion with whom he took walks, and though he was always available to the children who lived in his building, he was more of a recluse than the man who had captured the vibrant artistic life of early-20th-century Berlin just two decades before.

Yet…do we see the trauma of persecution manifested in Ascher’s later work? Or should we instead interpret his post-Shoah production as a gesture of resilience, a moving forward from the defining events of the past? To what degree should we balance the impact of trauma on Ascher’s artistic creations against the view that perhaps these later works instead betrayed hope, perseverance, and the resilience of a man who was ready to embrace the world’s beauty and freedom after so many years of fear and isolation?

We may never know with certainty the answers to the above, but what we can say with confidence is that Ascher’s work leaves plenty of opportunity for speculation.

DigiFAS Quick Clips

Interview with Ori Z. Soltes, September 2, 2020

“Fritz Ascher: Trauma and Resilience”

Elizabeth Berkowitz interviews Ori Z. Soltes, Georgetown interdisciplinary professor, about Fritz Ascher, the Cahana family of creators, and concepts of trauma and resilience in artistic creation. Topics discussed include the role persecution under National Socialism may or may not have played in Ascher’s later works, how hindsight impacts art historical assessments of both trauma and artistic purpose, and how art created after trauma may primarily demonstrate an artist’s ability to progress beyond oppression rather than remain constricted by the memory of it.

Expressions of Hope, or Residuals of Trauma? Fritz Ascher’s Later Works