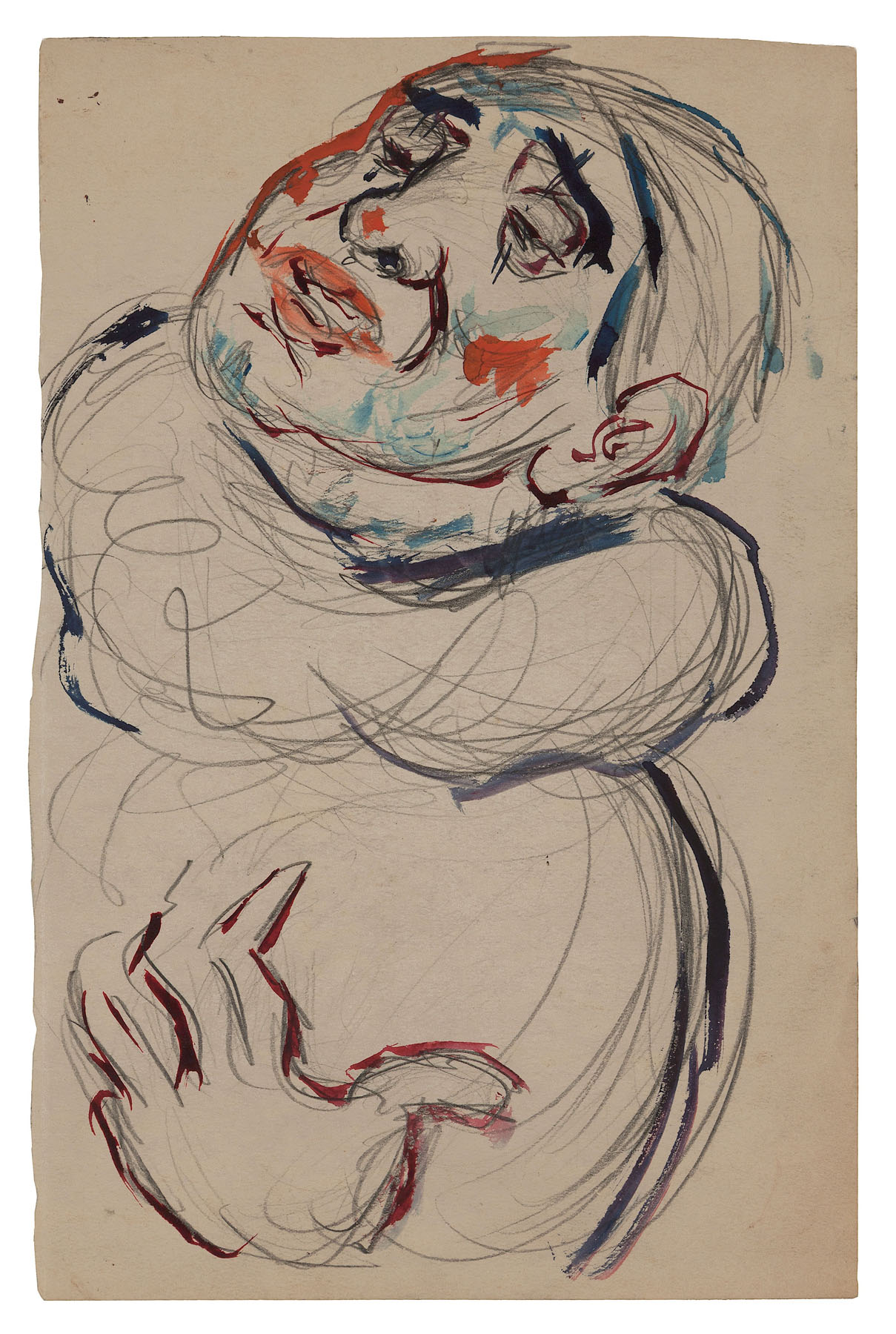

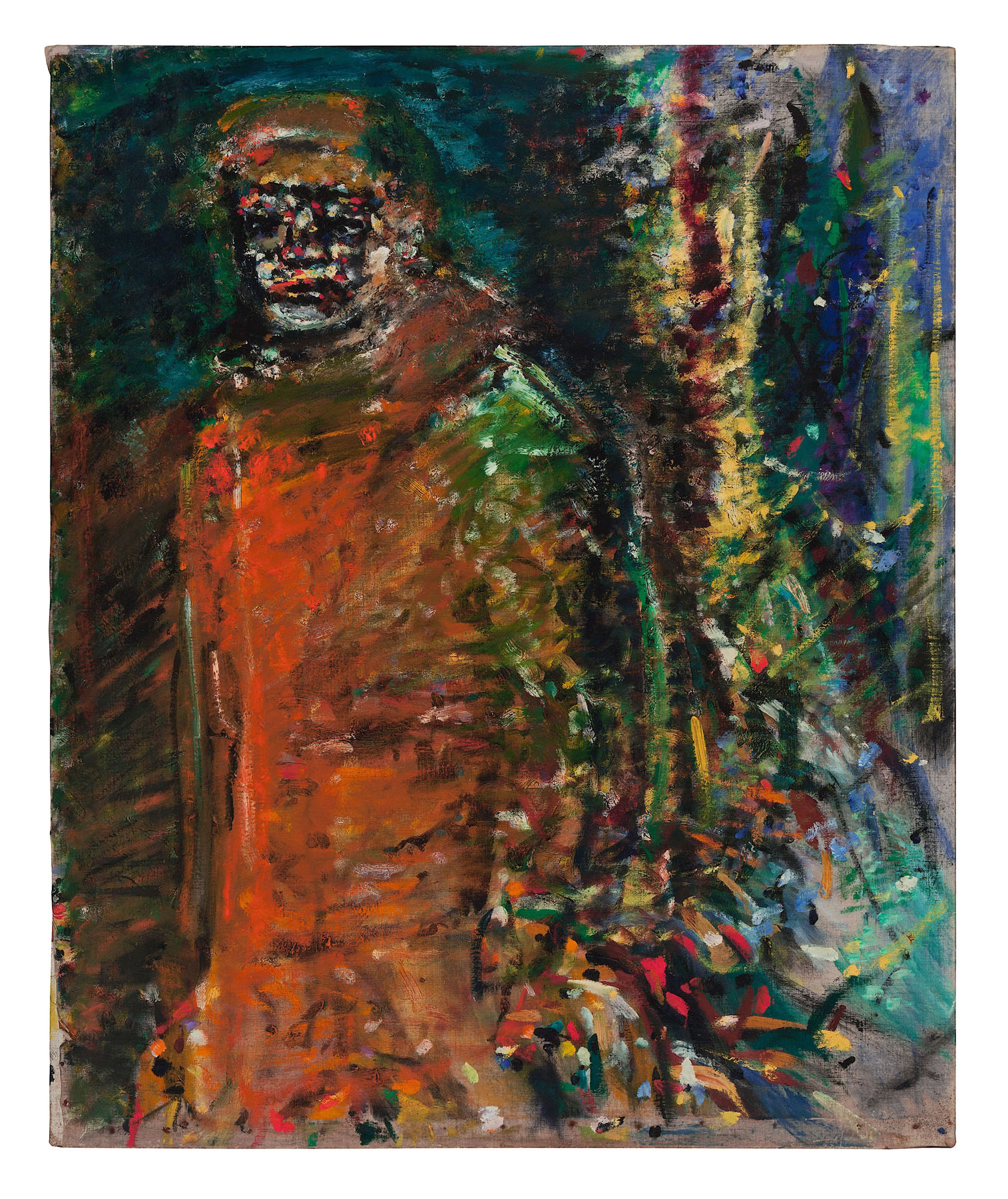

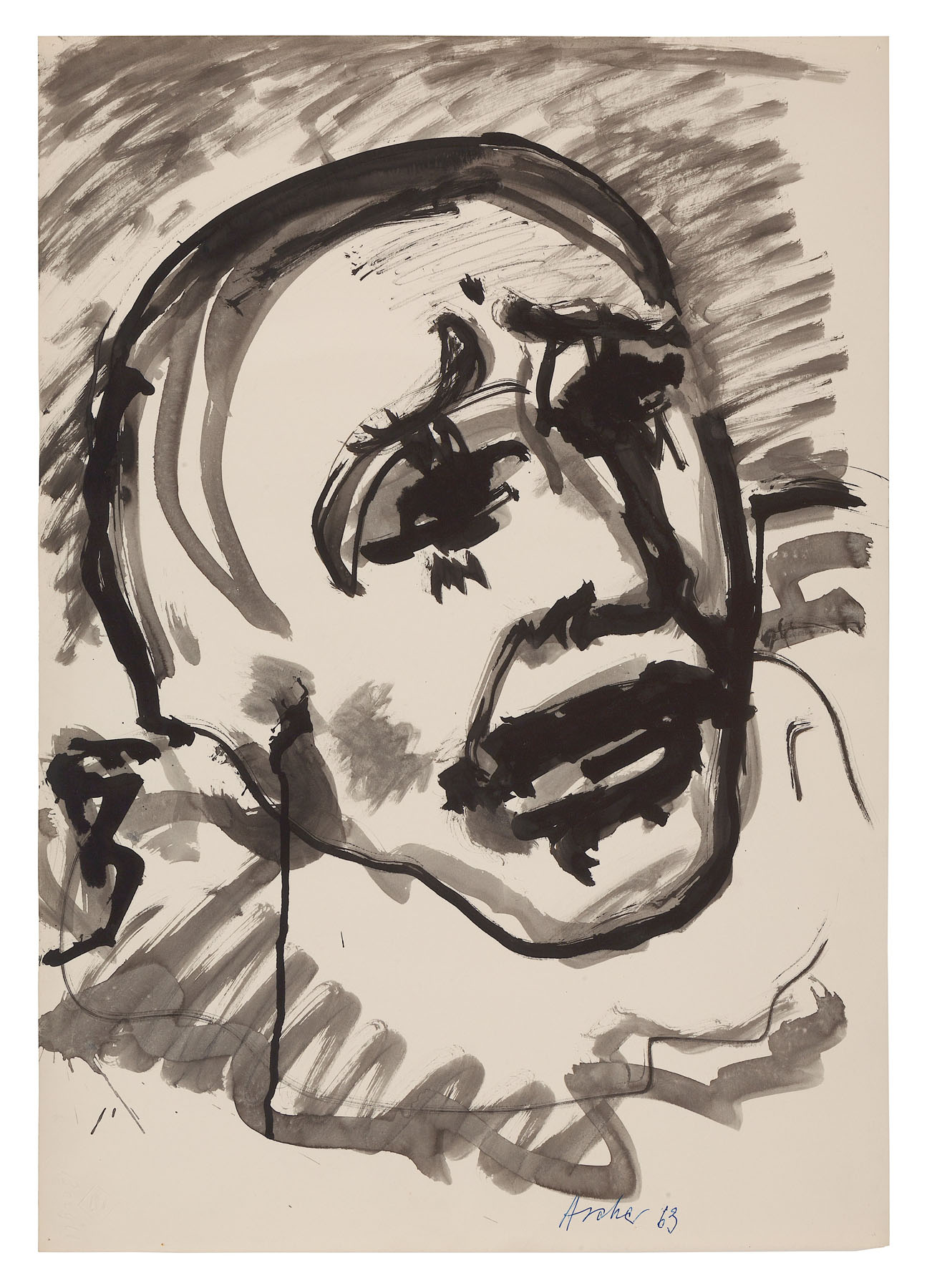

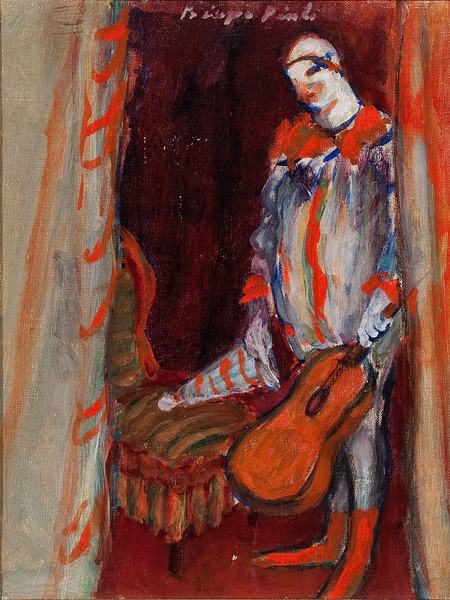

Of his extant body of work, both before and after the Nazi regime, Ascher created 22 pieces focused on the subject of “the clown.” The reasoning behind his interest in the subject is multi-dimensional, and reflects Ascher’s biography and life in a cosmopolitan early-20th-century Berlin, the interest among his modernist peers in depicting the clown figure, as well as the signification of “the clown” to an artist who was deeply concerned with representing the various facets of psychological experience on canvas.

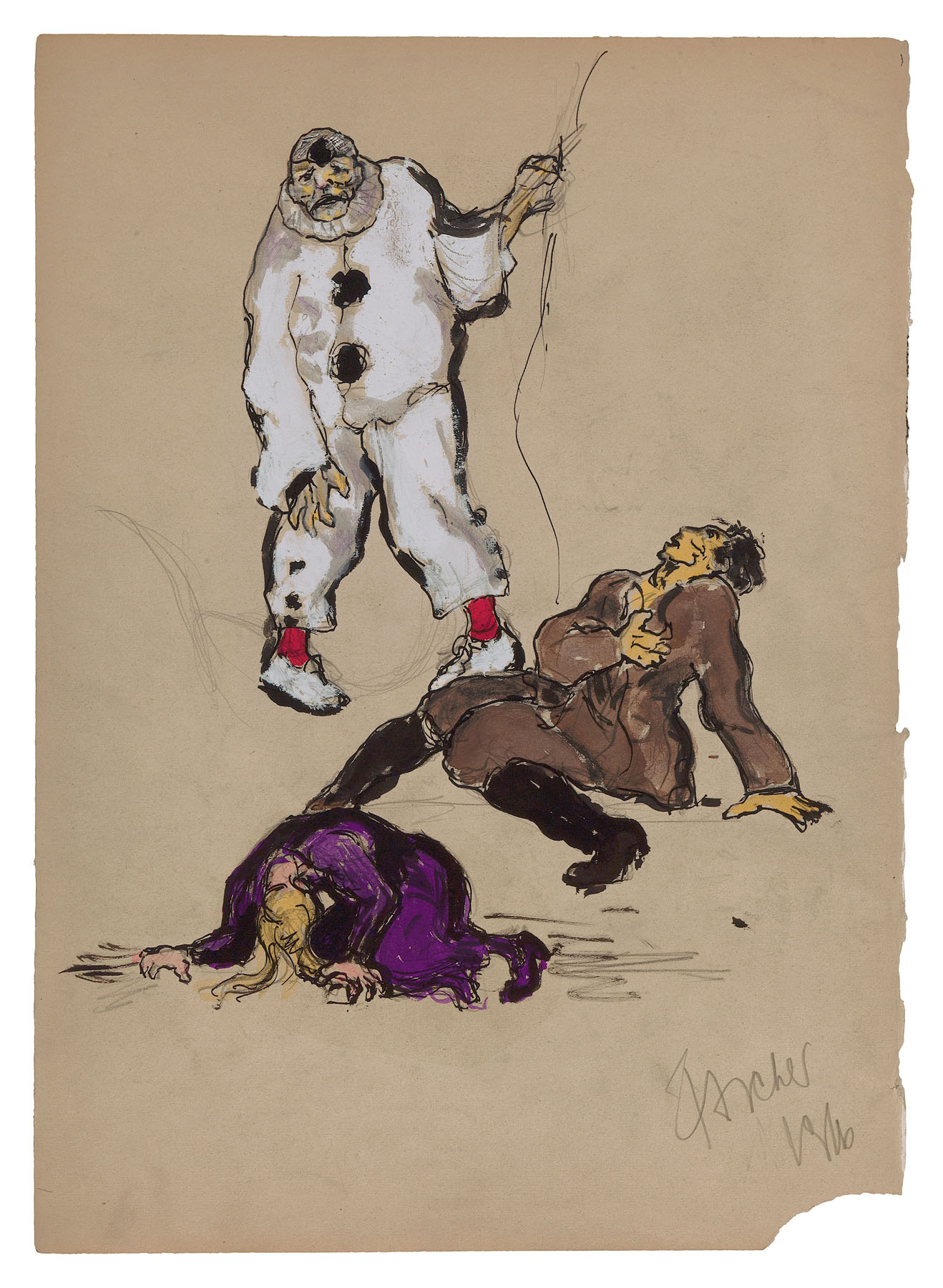

In 1913, the Royal Opera in Berlin staged a renowned performance of Ruggero Leoncavallo’s 19th-century opera I Pagliacci (Clowns). It is more than likely that Ascher, a devotee of music, saw this production, as his works such as Pagliaccio (1916) directly recreate moments from the opera. A story of the porous boundaries between art and life, the agony of having to conceal the pain one feels behind a mask—the comedic clown performing his own happiness—as well as the disastrous consequences of acting on those long-bottled-up feelings, are all themes in I Pagliacci ripe for an artist keyed into the Berlin art scene of the early-20th-century to plumb for inspiration.

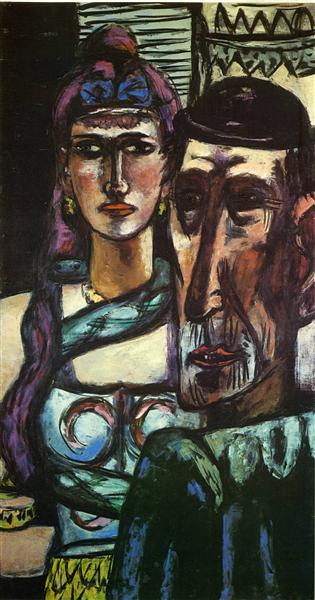

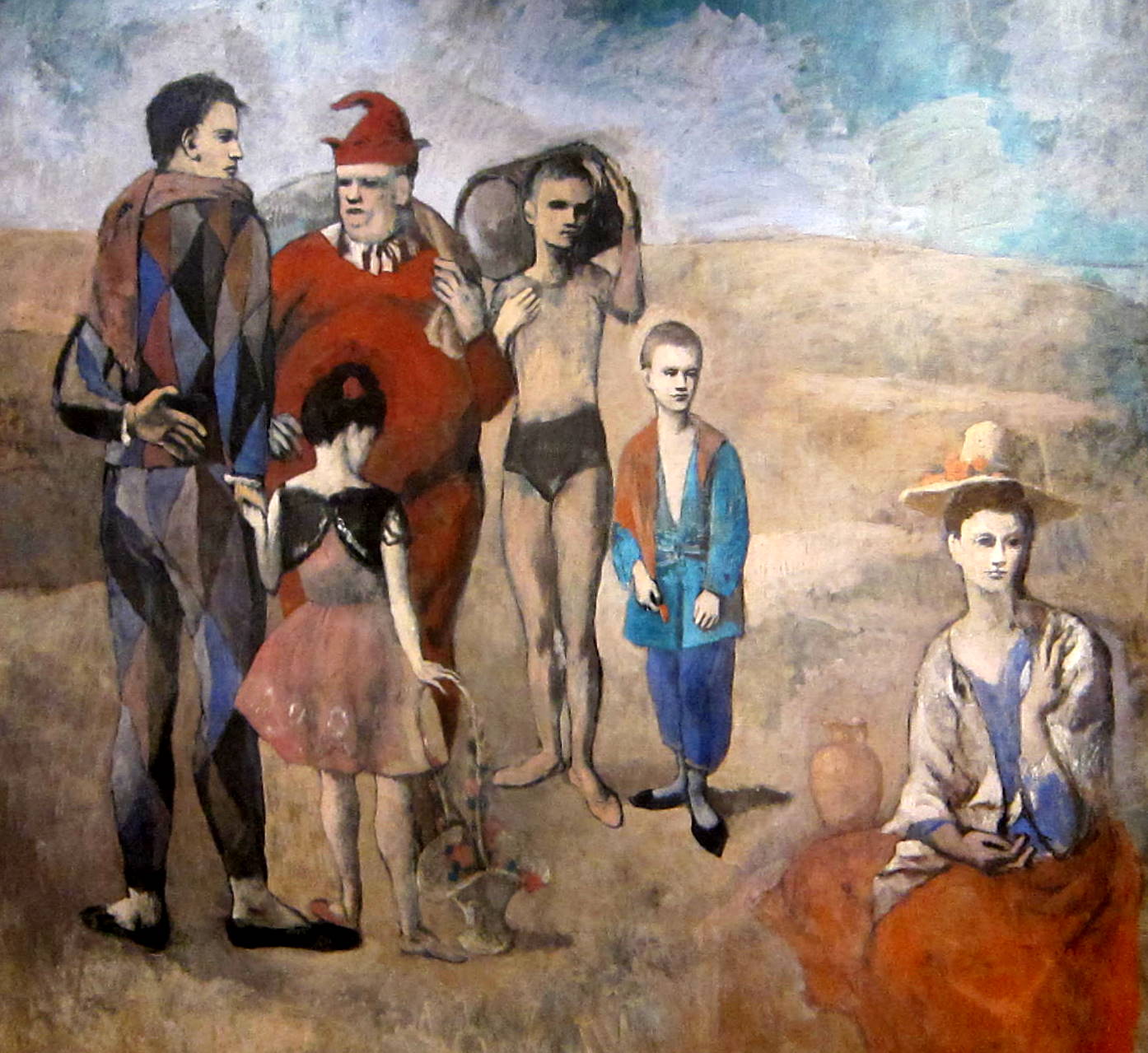

Ascher’s interest in this theme also extends beyond his personal experiences in Berlin and encompasses the wide range of modern artists who engaged with the idea of the “clown” both before and after the First World War. From Pablo Picasso’s saltimbanques to Gino Severini’s commedia dell’arte subjects, the clown and its presentation in popular culture was an important vessel through which modern artists explored ideas about performative emotions, fantasy vs. reality, and the paradox of sadness in a being conceived solely for entertainment and amusement. Ascher’s clown works further align him with the predominant artistic concerns and concepts of his day.

And, finally, Ascher’s interest in the subject of the clown—particularly when one considers the prevalence of the subject before and after Nazi persecution, as well as his poetry related to the clown figure—represents an extension of his exploration of the inner life. The clown, both in I Pagliacci and in other popular representations, can be an inherently tragic persona. The individual whose job it is to entertain, to project eternal happiness, to make people laugh, inevitably belies the sadness or torment or negative feelings equally experienced by a human being. The clown’s need to perform happiness in the world despite inner feeling to the contrary provides a perfect foil for an artist like Ascher to convey the contrast between how a person presents him or herself in public, and the unknowable (to others) inner life, which might be in direct contrast. With this and other interpretations of the clown similarly apt, Ascher’s continued engagement with the clown figure provided him an opportunity throughout his career to directly confront the representation of mental states.

DigiFAS Quick Clips

Fritz Ascher’s Clowns

The Clown in Modern Art

The motif of the clown–the person intended to always entertain and spread joy, but who, behind the “mask,” suffers from sadness and anger–was a commonly explored motif among artists and musicians, preceding and succeeding Ascher’s time.

Fritz Ascher’s Poetry

BAJAZZO

Narr der ich bin,

Topaz der Masse.

Ihr blödes Lachen

treibt mich her.

Je toller wird mein

Spiel = Grimasse –

Je mehr ich grolle, –

kreischt es höhr.

Ich fühle wie

der Hund die Streiche,

der wehrlos an

der Kette zerrt.

Pein krampft zu Schmerz -,

die Seele weint.

Und Tod und Trauer

schleichen.

(Buch 2, 1942-1945, S. 211, Nr. 376)

BAJAZZO

Fool am I,

the amusement of the masses.

Their stupid laughter

pushes me here.

The more absurd my play = grimace =

the more I rumble resentfully, –

The shrieks grow shriller.

I feel as

the dog does the lash,

that weaponless

tugs on his leash.

Agony convulses with suffering -,

My soul weeps.

And death and mourning

Prowl.

(Poems Vol. 2, 1942-1945, p. 211, no. 376)

Explore Further

All Fritz Ascher Images © Bianca Stock.