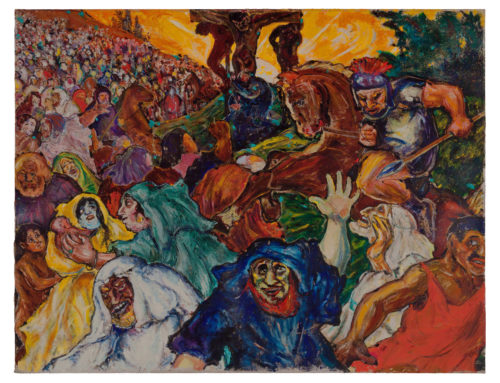

“Der Golem” (“The Golem”), 1916

The Golem was a creature said to have been contrived of earth from near the river outside Prague by Rabbi Judah Loew (1527-1609), an expert in esoteric Jewish mystical formulae. The Creature was a forerunner of Mary Shelly’s Frankenstein, of sorts: he was designed specifically to help the rabbi with everyday tasks (like gathering wood for the fire or bringing water from the river) and to protect the Jewish community from Christian predators. But only Rabbi Loew knew how to control him, and one day things got out of hand when the rabbi was away on a trip, so when returned he decided that he had to remove the it/him from circulation. The story became enormously popular in both Jewish and non-Jewish circles in the late 19th/early 20th century though renderings in both Yiddish and German, the first by a Jew named Yudl Rosenberg, the second by a non-Jew named Gustav Meyrink, who was part of the pre-World War I cultural circle that included Ascher. The artist presents the Golem itself with an expression of both fierce seriousness and sadness; the other three individuals—Rabbi Loew, presumably, in the center, flanked by his flowing white beard and his two assistants—have rather ghoulish expressions, noticeably limited teeth, and inordinately large hands.

Where the Golem looks out directly at us they all look down and to the side, as if either distracted and afraid of something (could they see some vicious anti-Semite, such as the Priest, Thaddeus from the Rosenberg version of the story, off to the side?) that we cannot see; or they are unable or unwilling to lift their gaze and look us in the eye.

The Golem looks more human than they and they look almost demonic. So he has reversed the norm and the expectation. Does this reflect a conscious or unconscious anti-Jewish bias, not to be unexpected necessarily for someone who is in the midst of trying to clarify his own identity as a Jew and/or as a Christian? But if Ascher’s depiction of the Golem it/himself is benign—who towers over the other individuals in the image, perhaps even protectively (hence the ferocity of his expression as he looks at us)—that also suggests that he is seen as a positive figure regardless of how those who made him and would ultimately have to destroy him were seen by the artist. This certainly accords with a distinct Jewish perspective. For Jews, the Golem was a kind of localized messianic character. The film scholar, Heide Schönemann, asserts that Ascher’s figures “are shaped in a manner suggesting Eastern European Jews, with keepot [skullcaps] and long robes, grouped before a background of big-city buildings that for Berliners would have appeared as typically Eastern (European.)” In other words, Ascher may be interpreted to have absorbed, as had many assimilated Jews, the Christian view of “stereotypical Jews”—meaning those from Eastern Europe—as fundamentally alien: as other. If Schöneman is right, then the threat that Jews pose to “us Germans” has been visually transposed as the threat that Eastern European Jews (because they are so shtetlized and unassimilated in their ways, including their garments) pose to “us German Jews.” How might we see Ascher’s Golem as falling between the kingdoms of darkness and light? Meyrink describes the Golem as having a golden face-color, with weird eyes, and refers to golden earrings worn by Jews—which is how Ascher has depicted them. What is the main color of the Golem’s skin in Ascher’s painting—and how might that relate to color symbolism in Christian art? And if we look at this work with its intense emotional quotient, and if we understand ambiguities in Ascher’s sense of self that are expressed on this canvas and others—and if we accept that ambiguity as articulated on this particular canvas by a vision of the protagonists that is not altogether positive but of the Golem itself as something with local messianic potential—then we might also ask how the messianic concept in general was understood or treated by Ascher. How else, if at all, did he reflect on the messianic idea in his work—as, for instance, in the painting, Golgotha? How does the Golem compare, on the other hand, to The Loner, both visually and conceptually?