Ori Z. Soltes. Tradition and Transformation. Three Millenia of Jewish Arts and Architecture.

Boulder, CO: Canal Street Studios 2016.

pp. 165, 302-303

p. 165

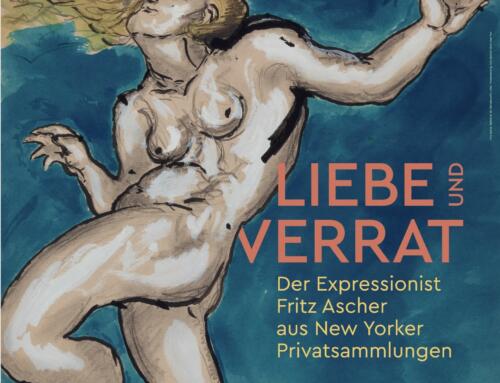

The issue of Jewishness and being Jewish brings this chapter full circle back to Berlin. There Fritz Ascher (1893-1970) came of artistic age with his powerful 1916 painting of “The Golem.”

Ascher’s father, Hugo, decided to convert to Protestantism with his children in 1900/1901. It seems likely that the issue was also less one of spiritual conviction than of socio-economic and political convenience or even concern for the safety of his children and their future. Hugo’s wife did not convert—for a quarter of a century (1926), four years after her husband died—and it is not entirely clear why she did so then.

How did young Fritz view himself vis-a-vis his Jewish/non-Jewish identities? When he was deported to Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp on Kristallnacht, it was for political subversion, not for being Jewish, and it is not clear whether, when he later went into hiding for three years, the deportation that he sought to evade would have been based on his Judaism—although that seems likely—or because he was still considered artistico-politically subversive. Was it as a Jew that he was in danger: because the regime would have seen him as a Jew regardless of his childhood conversion?

Chronologically sandwiched between his conversion and his Sachsenhausen experience, Ascher paints his Golem with an expression of both fierce seriousness and sadness; the other three individuals—Rabbi Loew, presumably, in the center, with his flowing white beard, and two assistants—have rather ghoulish expressions, noticeably limited teeth, and inordinately large hands. Where the Golem looks out directly at us, they all look down and to the side, as if either distracted and afraid of something or unable or unwilling to look us in the eye. The Golem looks more human than they and they look almost demonic. So he has reversed the norm, making his Golem more human and sympathetic than his Jewish makers. Does this reflect an (un)conscious anti-Jewish bias?

If Ascher’s depiction of the Golem is benign—towering over the other individuals, perhaps even protectively (hence his fierce expression as he looks out at us)—that also suggests that he is seen as a positive figure, even as those who made him and would ultimately have to destroy him are perhaps seen negatively. This affords a Jewish perspective. The Golem as a light, not dark figure, is messianic, albeit on a local level. Ascher perhaps embraced this idea, in part, even as his painting overall does not offer a positive view of the Jewish leaders. So we see a work with an intense emotional quotient, arguably reflecting ambiguities in Ascher’s sense of self that are expressed on the canvas—by a vision of the protagonists that is not altogether positive but of the Golem itself as something with local messianic potential.

FIG 175: Fritz Ascher: The Golem, 1916. Jewish Museum Berlin GME932 ©Bianca Stock

We might ask how the messianic concept was otherwise treated by Ascher. He did several portrayals of Christ, in fact. About a year before his Golem painting he shaped an odd image of Golgotha, followed, later, by other very ideosyncratic Christocentric images. In part he furthers a tradition begun by Jewish artists like Antokolsky and Ezekiel which will reach a crescendo with Chagall, as we shall see in the chapter that follows this one. In part he simply handles that subject in a uniquely idiosyncratic manner.

The reference to Chagall anticipates how definitional difficulties intensify as we move West and enter Paris—as some of these artists briefly did and some would for the remainder of their careers, and Chagall certainly did for important and long stretches of his life and his career—beginning in the first decades after 1900, during the period of that city’s zenith as a center of both traditional culture and artistic invention. We turn next to the City of Light as a magnet for artists, Jewish and otherwise, as the twentieth century continues to unfold.

pp. 302-303

This anthropocentric perspective is largely the opposite of that taken by Fritz Ascher as he emerged out of three years of hiding in a bombed-out Berlin villa basement, cared for by a friend of his mother, Martha Grassman. During that time, bereft of materials with which to paint and draw he had turned to the word, writing very dense and difficult poetry. From shortly after the war until his death in 1970, however, he turned back to oil painting and drawing.

For the most part, he turned, in his oils, away from figurative images, (away from human beings, one might say, after surviving an era of unprecedented human-contrived abominations), toward landscapes and nature that are both richly textured and vibrantly colored—even his darknesses seem to have a paradoxic brightness to them—although in his drawings and water colors and gouaches, figures and often very fierce faces remain prominent. One of these is perhaps another image of the Christian messiah in the penultimate moment of the earthbound, human part of his infinite journey. It is a late gouache and watercolor from 1961, in which Ascher depicts a woman with the head of a man in her lap: it may be seen as the detail of a pieta, where the woman is the Virgin Mary and the man is the Jesus who is mourned by his mother, her eyes and mouth deep pools of blackness as she silently cradles the head of her son. Even in the restrained limitations of grays and blacks the image seethes quietly with emotion that is both specific to the Christian narrative and universal: this could be any mother or wife holding any son or husband who has died before he should have—due to war or some other cause.

In his oils, Ascher depicts the sky itself and depicts the sun exploding from the canvas toward the viewer. Or the viewer is the sun, turning toward the sunflowers that fill the entire picture plane, that turn toward the sun, as the artist portrays these elements, one by one, canvas by canvas, in thick, bright colors that suggest both vibrant, life-affirming joy and, in the rough-hewn nature of his brushstrokes, a dark, inner anguish transformed into light. In the last decade of his life he often used the motif of two lush trees rising toward a sky that scintillates with light blue and is dominated by white, fleshy clouds; or that glows, in an evening landscape, from horizon line to treetops to the upper edges of the painting with the same sort of brash yellow-orange that he used decades earlier on Christ’s halo in his mysterious image of Golgotha. Are the two trees (or two lines of trees) that repeat so often simply two trees to frame the sky to which he devotes such visceral attention, or do they echo the spiritual duality—feeling somehow both Jewish and Christian—that haunted the artist throughout his life?

FIG 342: Fritz Ascher: Two Trees in the Wind, 1961. ©Bianca Stock

As life sometimes imitates art and art reflects on life, one might say that it was inevitable that ordinary people could and did assume gigantic villainous and heroic proportions in the context of the Holocaust that left Ascher’s brush vibrating; and could and did sometimes assume heroic proportions in an event like the founding of Israel, to the recording of which Capa devoted such extensive effort. It is to the art taking shape in that corner of the earth before and during that founding process that we direct ourselves next.