If not for the Nazis, he may have been the next Leonardo

German Expressionist painter Fritz Ascher survived the Holocaust, but his career never recovered. A new foundation is trying to change that

by Cathryn J. Prince

NEW YORK – “Artist, interrupted” — two words that describe the accomplished German Expressionist painter Fritz Ascher, a Berlin-born artist who was persecuted, ostracized and banned under the Nazi regime.

But now, if Rachel Stern has her way, Fritz Ascher will be “artist, re-discovered. “The intensity, the strong energy, the colors, the forms,” Stern said recalling the first time she saw his work in the mid-80s. It was love at first sight. In fact, Ascher’s work so touched Stern she started researching the artist’s life. She delved into archives and knocked on the doors of Ascher’s former neighbors. Ultimately, she founded the New York-based Fritz Ascher Society for Persecuted, Ostracized and Banned Art, Inc. “I hope with my foundation to show you can survive these regimes and still have your voice. That’s a very important message for today,” Stern said.

Ascher survived the war, but in many ways the suppression of his work continued, Stern said. In the first few decades after the war few people wanted to talk about looted or displaced art or the fate of the artists themselves, she said. Consequently many artists such as Ascher remained unknown for decades.

It wasn’t until the 1990s, that people began addressing the systematic looting of art from museums and private collections. Lynn Nicholas’s 1995 book, “The Rape of Europa: The Fate of Europe’s Treasures in the Third Reich and the Second World War,” contributed a great deal to the discussion.

Stern herself immigrated to the United States from Berlin in 1994. She went to work at the New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art where she was responsible for the administration of loan exhibitions in the Department of Prints and Drawings. Then in 2010 Stern decided if she didn’t take on the Ascher project full time it might possibly slip from her grasp forever. She resumed her research and connected with a collector of Ascher’s work. He encouraged Stern to take up the mantle of Fritz Ascher. “I have this sense of obligation to have people see this artist. It seems to be the right time to introduce people to Fritz Ascher,” she said.

The foundation is preparing to launch its first exhibition in 2016. The comprehensive retrospective of Fritz Ascher’s artwork will unite early drawings and paintings from 1910-1930 with mature gouaches and paintings from 1945-1970. Four German museums, including the Kunstmuseum Solingen and the Felix-Nussbaum-Museum in Osnabrück will show the retrospective. Afterwards it will travel to the US. The New York City-based Leo Baeck Institute is supporting the exhibition. The Kunstmuseum Solingen in Germany is the only museum to focus solely on the theme of degenerate art and persecuted artists, said Dr. Rolf Jessewitsch, the museum’s director. He looks forward to re-introducing Ascher to Germany. “There are a lot of very good artists who are not known today because their life was interrupted by the war,” Jessewitsch said. “Artists such as Ascher were too young to gain a following when war broke out.”

Born in 1893 in Berlin to Dr. Hugo Ascher, a dental surgeon and businessman, and Minna Luise Ascher, Fritz Ascher had two younger sisters. Ascher’s father converted to Protestantism in 1901, but his mother remained Jewish. The children all were converted as well. The decision was likely made less for religious conviction than it was for socio-economic considerations, Prof. Ori Z. Soltes, Founding Director of Fritz Ascher Society and Professor at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C. “As much as we talk about assimilation and acceptance, the German world was closed for most Jews,” he said.

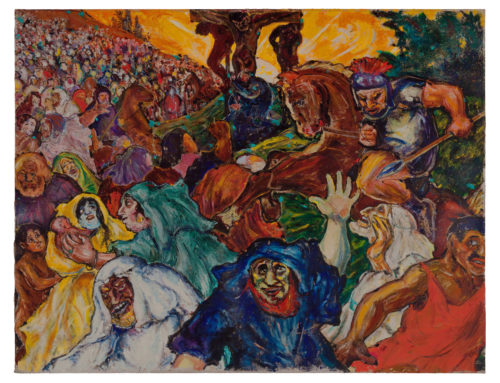

Ascher’s parents recognized talent in their son. When he was 16 they sent him to study under Max Lieberman, a celebrated 20th Century German Jewish master. Lieberman recommended Ascher to the art academy Königsberg in East Prussia. In 1913, Ascher returned to Berlin. An “emphatic and expressive religiosity” marks his work during this period, Stern said. The best examples of this are his 1916 “Golem,” now hanging in the Jewish Museum in Berlin and his 1918 “Crucifixion.”

“I think he was spiritually someone who definitely believed in a higher power,” Stern said. “But where does he stand religiously? How did he relate to being Jewish?” That question may never be answered, Soltes said. Ascher was raised in a secular household and left little to indicate his views on Judaism. His subjects, save for the “Golem,” were not particularly Jewish. Focusing on an artist such as Ascher raises provocative questions about what is meant by “the phrase Jewish art,” Soltes said. “Is it that the artist was Jewish? Or is it the style of painting? Or is it the subject?”

Shortly after Adolf Hitler became Chancellor in 1933 Ascher was reported to the Nazis as politically and artistically subversive. As a Jew he could no longer purchase art supplies or sell his artwork. With the stroke of a pen Ascher was stripped of his avocation. On Kristallnacht Ascher was arrested and deported to Sachsenhausen concentration camp. From there he was transferred to Potsdam prison. Six months later Ascher walked out of Potsdam, thanks to the efforts of his attorney friend Gerhard Grassmann and Probst Heinrich Grueber, an Evangelical Protestant minister. His freedom, such as it was, was short lived. In 1942 the Nazis again threatened him with deportation. This time he turned to Martha Grassmann, a close friend of his mother. For three years Grassmann hid Ascher in a partially bombed-out villa in the heart of Berlin, right in the midst of high-ranking Nazis.

With no means of painting, poetry became Ascher’s creative outlet.

Then came V-E Day and Fritz Ascher came out of hiding. He moved back to Berlin and resumed painting, prolifically, until his death in 1970. But something was different. Gone were the monumental figurative compositions that marked the first phase of his career. Now he turned out dense landscapes with blood orange sunsets and jet-black tree trunks against midnight blue skies. “Through his late landscapes he somehow came into his own. He really found his artistic voice,” Stern said.