Dear Friends,

What was it like to be a Jew in Nazi Germany? Come join the discussion tomorrow, February 12, at 6:30 pm, when I speak with Marion Kaplan, Skirball Professor of Modern Jewish History, NYU, about those who went underground, including Fritz Ascher, and endured the terrors of nightly bombings, hunger and cold, and the even greater fear of being discovered by the Nazis. At King Juan Carlos I of Spain Center, 53 Washington Square South.

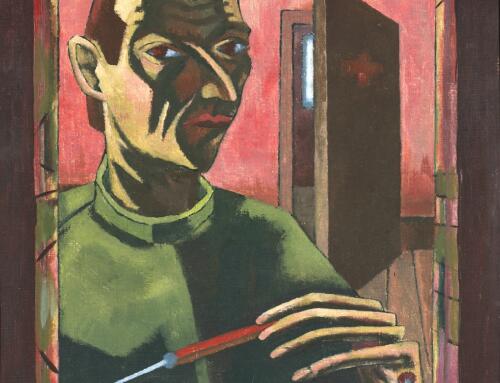

This program accompanies the exhibition “Fritz Ascher, Expressionist” at the Grey Art Gallery of New York University here in New York – please check out the other stimulating programs here. And do not forget to see the exhibition, which is on view until April 6.

You can find more installation photos of the exhibition on our website.

“We can now safely add him to our canon of 20th-century German artists,” wrote Tom Freudenheim in the Wall Street Journal about Fritz Ascher, who is “Finally home with the Greats.” (link)

Like the previous exhibitions, the one at the Grey Art Gallery brings forth new exciting scholarship. Moderated by Rose-Carol Washton Long, the panel discussion “European Modernism and Spirituality” at the CUNY Graduate Center on January 30th provided much food for thought – stay tuned for our video recording of the event!

Thank you, Elizabeth Berkowitz, for opening our eyes to the possibility of Fritz Ascher using occult-inspired symbolic color in his early work. Interest in the occult was prevalent in the interwar period, and artists surrounding Fritz Ascher like Wassily Kandinsky, Edvard Munch and August Strindberg were deeply influenced by Theosophical writings with the idea that color signifies emotional states, feelings or worldviews.

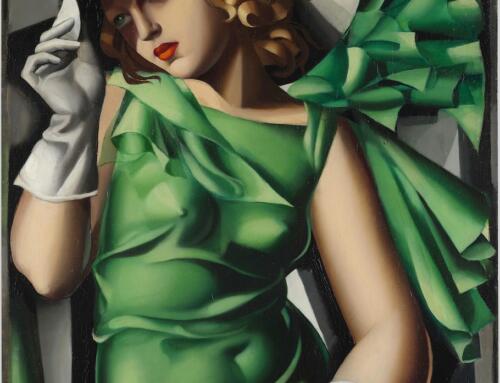

Viewed in this context, Ascher’s monumental painting The Tortured shows “the inner struggle of the central figure as a quest to realize his ideal, spiritual potential amidst the conflicting forces of vice and more unsavory impulses. The central male figure, strong, able to physically but not emotionally break the restraints that hold him, is blue—the color of religious fervor, divinity, spirituality. His tormenters then include uncontrollable anger or passion (red). His intellect (yellow) holds him back from realizing his spiritual ideal. The purple woman, as desire and devotion, is a distraction that whispers in his ear, or an “unsettling” influence, using Goethe’s view on purple. The slightly menacing, monstrous woman is rendered in Goethe’s ideal color combination—the peaceful equilibrium of green threatened or tempered by the menace of red passion. That individuals of varying ages and genders should manifest the central male figure’s inner psyche only confirms the occult links between Ascher’s color choices and a symbolic color palette, as in Theosophically inspired art, the duality of the universe was often expressed as the alignment of male and female impulses.”

This interpretation underscores Munch’s artistic influence on Ascher. It just became much easier to look deeper into that relationship, because Munch’s works on paper, some 7,600 drawings, were digitized by the Munch Museum in Oslo and are now available online.

Something fun to do once winter hits and you do not want to leave the house!

Warm wishes,

Rachel Stern, Director and CEO

artwork Fritz Ascher ©2019 Bianca Stock, Photo Malcolm Varon