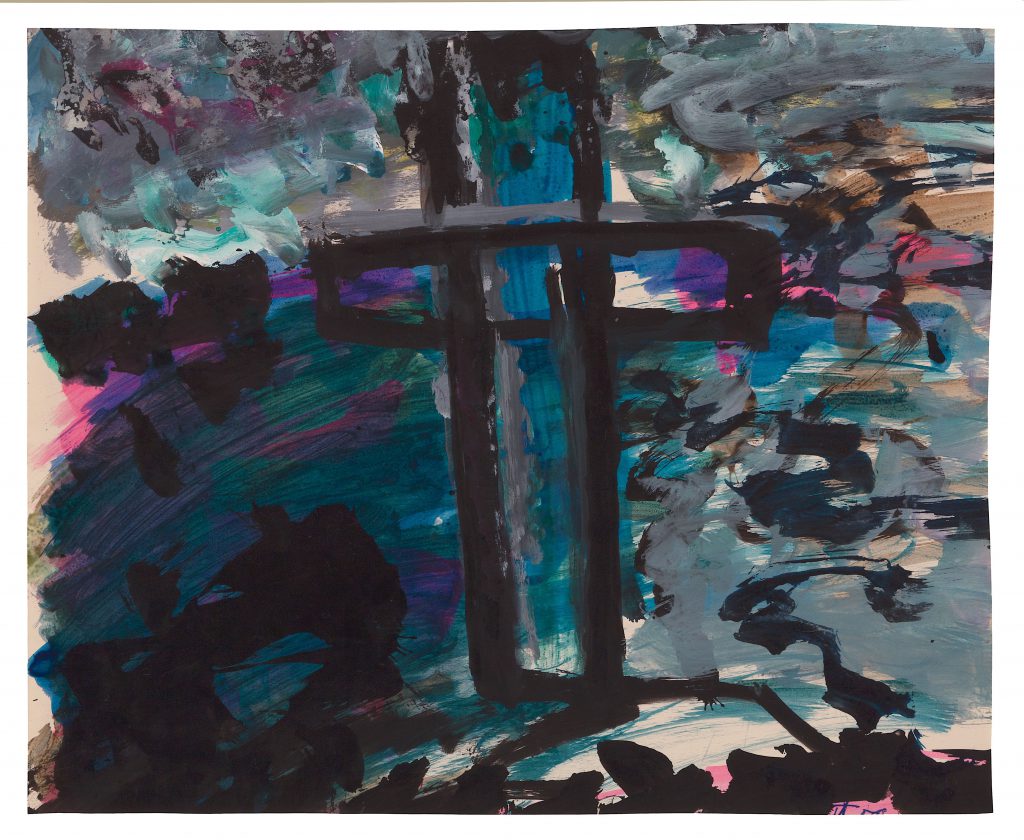

Cross (Suicide Cemetery Grunewald), c. 1957

This work on paper is a stylized representation of and reference to a specific cemetery in the Grunewald: the one to which those who had needed their lives by suicide—most of them, apparently, by leaping into the nearby Havel River—had been consigned since 1897, since suicides were not typically permitted burial in the consecrated ground of Christian cemeteries in and around Berlin. What might have drawn Fritz Ascher to that specific site in the vast acreage of the Grunewald? Why did he choose to depict that single cross and its visual context in such a stylized, non-straightforwardly representational style? What do you suppose motivated his choice of colors? This is the only “suicide cemetery” in Germany—and has been around since the late 19th century. Why had such a cemetery apparently not existed for so many centuries before or elsewhere—why would a suicide be denied burial in the family plot in the communal graveyard? Why would that issue become significant at such a time in German history? It might be interesting to research and compare the attitudes toward suicides in different traditions: for instance, among the pagan Greeks—especially in Plato’s day—and Romans, among the Jews, Christians, or Muslims—and are there differences among the sub-traditions within each of these three Abrahamic faiths: Reform vs Orthodox Jews, Catholic vs Lutheran Christians, Sunni vs Shi’i Muslims, for instance?