Back into the Light.

Four Women Artists – Their Works. Their Paths.

Lecture by Eva Atlan, PhD, Frankfurt (Germany)

January 11, 2023 @ 12:00 pm - 1:00 pm

| FreeErna Pinner, Rosy Lilienfeld, Amalie Seckbach, and Ruth Cahn were among the first women artists in Frankfurt to enjoy professional success. Throughout the Roaring Twenties, these four Jewish women left their mark on Frankfurt’s art scene, published and exhibited internationally, cultivated a cosmopolitan lifestyle, and competed with their male colleagues. When the National Socialists seized power, their careers came to an abrupt end. From then on, they were persecuted as Jews and their works ostracized; later, after the end of World War II, they were largely forgotten. Now, “Back into the Light” is at long last bringing them back to the public eye.

The departure point is an article by art historian Sascha Schwabacher, published May 1935 in the Frankfurter Israelitisches Gemeindeblatt, a German-language Jewish newspaper in Frankfurt. Schwabacher recalls her visits to the studios of the four artists and describes their personalities—at a time when these women had no more than limited job opportunities in Germany as a result of the persecution they suffered at the hands of the National Socialists. The lecture delves into these four studio visits, and in doing so, it brings the Frankfurt art scene of the 1920s back to life, making palpable the disruption Nazi rule meant for the four artists’ work and lives.

This lecture by Dr. Eva Sabrina Atlan is based on research for the exhibition “Back into the Light. Four Women Artists – Their Works. Their Paths” which is on view until April 17, 2023 at the Jewish Museum Frankfurt (Germany). Introduced by Rachel Stern, director of the Fritz Ascher Society.

Eva Sabrina Atlan, PhD, is deputy director of the Jewish Museum Frankfurt. Previously she was curator for art and Judaica (2005 – 2018) and then head of collections. She is curator of the exhibition “Back into the Light. Four Women Artists – Their Works. Their Paths.” After studying art history, classical archeology and Romance studies in Frankfurt am Main, she spent a research stay in Boston/USA, followed by her doctorate at the Johann-Wolfgang-Goethe University in 1997 on Samuel Bak. Work monograph from 1945 to 1990. In addition to the new permanent exhibition area Splendor of the Commandment, she is responsible for numerous exhibitions and publications, including as co-editor of Eternal Light. Samuel Bak. A Childhood in the Shadow of the Holocaust (1996), Access to Israel (2 vols., 2008) and 1938. Art. Artist. Politics”(2013) and as the author and co-editor of The Feminine Side of God. Art and Ritual (2020) and Back into the Light. Four Women Artists – Their Works. Their Paths (2022).

Amalie Seckbach, Hydrangea Blossom (Hortensienblüte) (original title not known), 1939. Oil on China paper, 33 x 24 cm. Buch Family Private Collection

Amalie Seckbach, 15.11.43 Theresienstadt (original inscription by artist), 1943. Pastel on paper, 24 x 16,5 cm. The Ghetto Fighters’ House – Itzhak Katzenelson Holocaust and Jewish Resistance Heritage Museum, Israel

Amalie Seckbach (1870, Hungen – 1944, Theresienstadt)

The German-Jewish artist Amalie Seckbach (1870-1944) moved with her parents from the town of Hungen to Frankfurt am Main in 1902. Inspired by Far Eastern philosophy and religion, she built up a collection of Chinese woodblock prints that was highly praised in specialist circles as early as the early 20th century. It was only later in life, after the death of her husband, the architect Max Seckbach (1866-1922), that she began to work as a painter and sculptor. As early as 1929 she was able to exhibit her sculptural works in an exhibition with James Ensor (1860-1949) at the Musée des Beaux-Arts as well as in exhibitions at the Salon des Indépendants in Paris.

From 1933 onwards, she could only exhibit in Germany within the parameters of the Jewish Cultural Association or abroad, as she did in 1936 at the Art Institute of Chicago. In 1941, when the Nazi regime persecution reached devastating proportions, Amalie Seckbach decided to leave Germany, but was arrested in September 1942 and deported to the Theresienstadt concentration camp. Here she painted with the materials at her disposal, but succumbed to the consequences of imprisonment in August 1944.

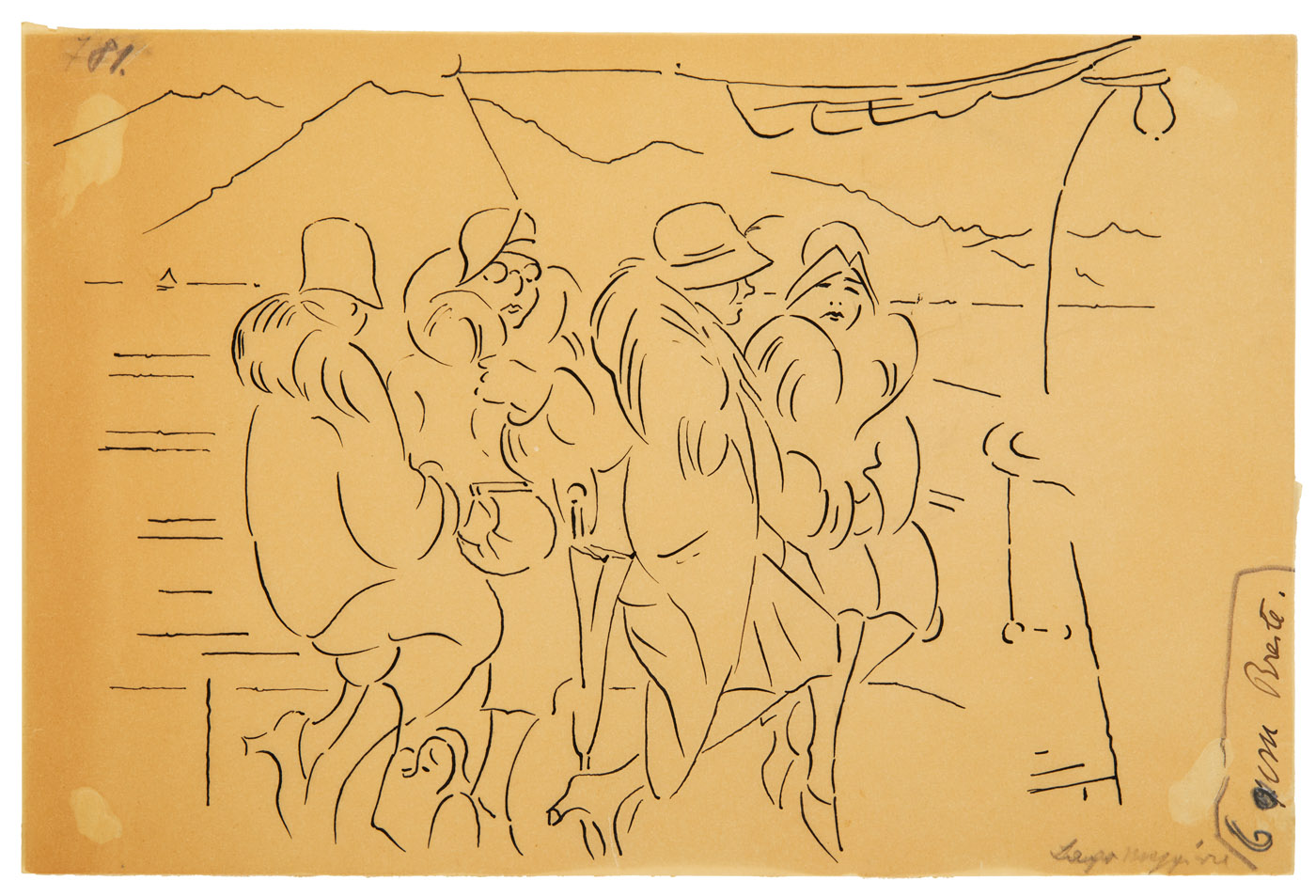

Erna Pinner (1890-1987), Four Women at Lago Maggiore (Vier Frauen am Lago Maggiore), 1925. Ink on transparent papir, 16,5 x 29,4 cm. Jewish Museum Frankfurt / Estate of Erna Pinner

Erna Pinner, William’s Jerboa (Williams’ Springmaus) (“Allactaga williamsi”), 1935 – 1948. Drawing, 11 x 15,5 cm. Jewish Museum Frankfurt © Estate of Erna Pinner

Erna Pinner (1890, Frankfurt am Main – 1987, London)

The exhibition sets out to juxtapose two fundamentally different phases of Erna Pinner’s life and work. In both phases, though, the focus is primarily on her oeuvre as a writer and illustrator. Erna Pinner gained public recognition in the 1920s with such publications as Das Schweinebuch (“The Book of Pigs”, 1922), Eine Dame in Griechenland (“A Lady in Greece”, 1927), and Ich reise um die Welt (“I Travel Around the World”, 1931). Through her illustrations, these books stand as quite independent works far removed from the influence of the expressionist writer Kasimir Edschmid. In them, she not only attained a graphic style with a precise and elegant use of line, but also effectively fused the seen and experienced with the written word.

After emigrating to London in 1935, she developed a new style of illustrations for popular science publications, depicting volumes, proportions, and textures in almost photographic detail. She studied zoology at university and took courses in printmaking. After the war, her publications increasingly dealt with the history of species. From the years after her emigration, two books especially provide an impressive example of her mix of artistic insight and scientific research – Curious Creatures (1951, 1953 in German) and Born Alive (1959).

Ruth Cahn, Palm House in the Palm Garden (Palmenhaus im Palmengarten), 1924. Gouache on paper, 88 x 68 cm. Historical Museum Frankfurt

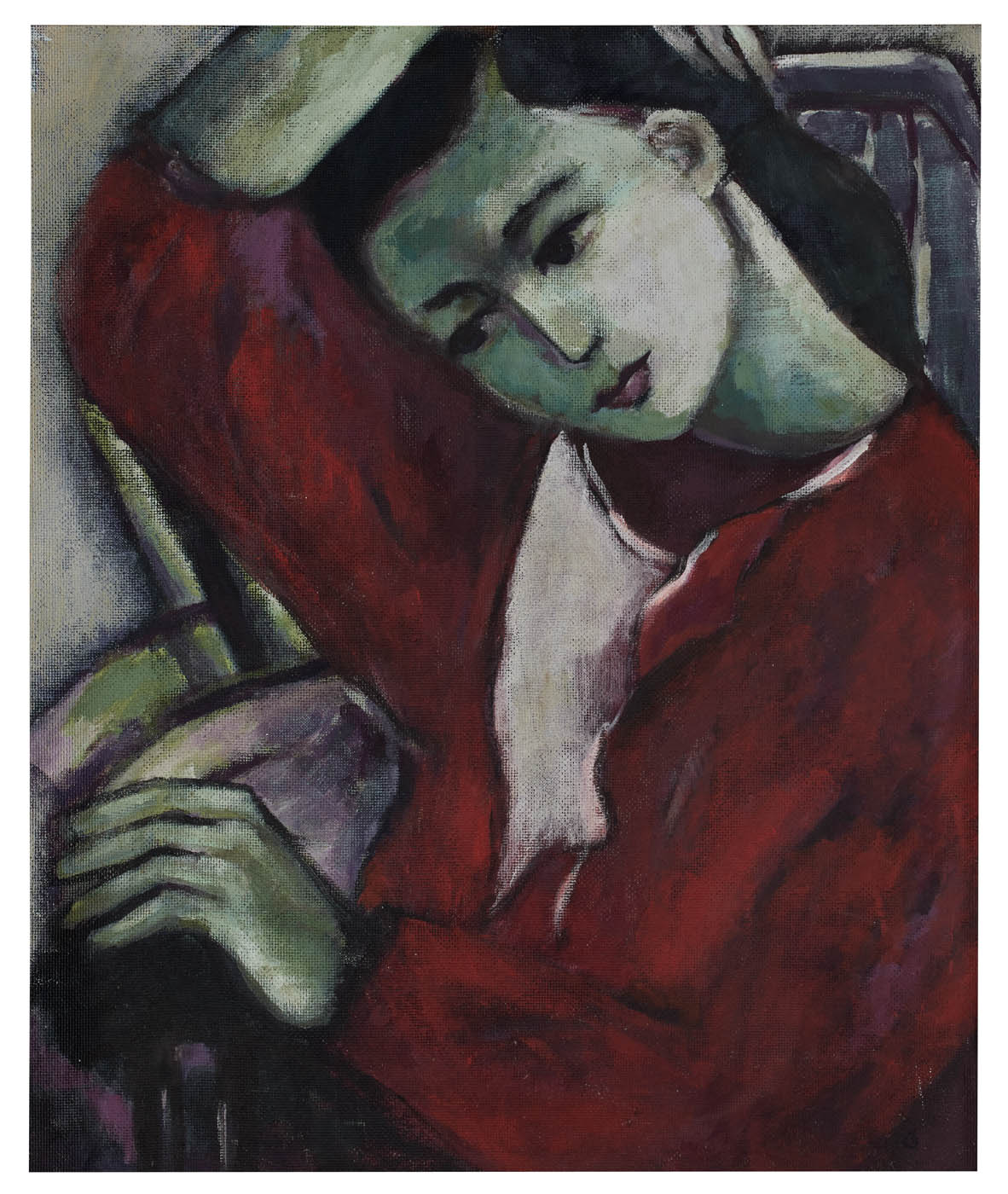

Ruth Cahn, Girl in Red Jacket (Mädchen in roter Jacke), 1920-1935. Oil on hardboard, 57,5 x 47 cm. Edition Memoria, Thomas B. Schumann, Hürth, Germany

Ruth Cahn (1875, Frankfurt am Main – 1966, Frankfurt am Main)

Born in Frankfurt am Main in 1875, the artist Amalie Leontine Cahn became known far beyond her hometown as Ruth Cahn. She studied art in Munich and Barcelona, and in particular with the Fauvist painter Kees van Dongen in Paris. In the 1920s, her paintings were shown at the Frankfurt art dealers H. Trittler and Ludwig Schames. In 1924, the Dalmau Gallery in Barcelona presented Ruth Cahn’s pictures in a solo show. The same gallery also enabled Joan Miró and Salvador Dalí, then unknown artists, to have their first shows.

Ruth Cahn’s family was scattered across Spain, Switzerland and South America. In 1935, she emigrated from Nazi Germany to Chile, only returning to Europe in 1953. After living in Barcelona for some years, she moved back to Frankfurt in 1961. She died in her hometown five years later. Today, the vast majority of Cahn’s oeuvre is thought to have been lost in the turmoil of the Spanish Civil War and the Second World War. We would like to reconstruct Ruth Cahn’s life and work. She belongs to that generation of Frankfurt German-Jewish women artists whose creative work was abruptly halted.

On 8 September 1984, the Frankfurt Arnold auction house sold two of Cahn’s paintings. Since then, all trace of them has been lost. Does anyone know where they could be now?

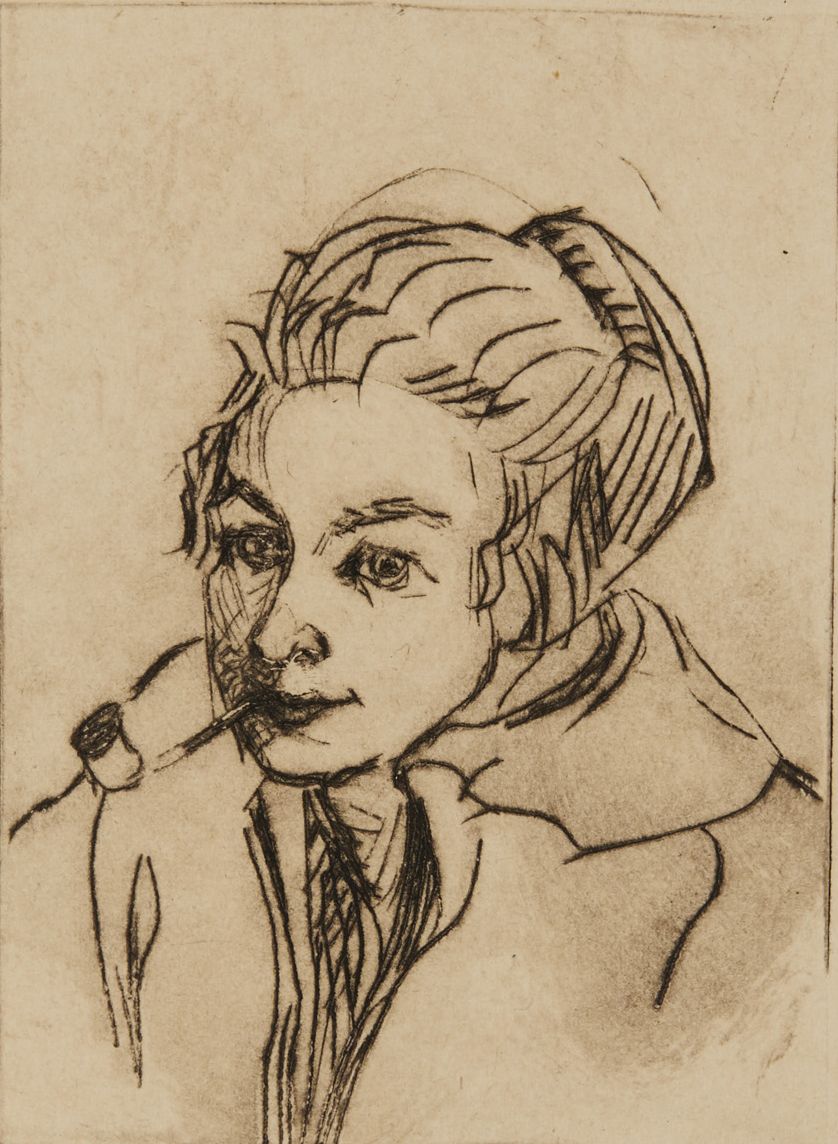

Rosy Lilienfeld (1896-1942), Woman Smoking a Pipe (Frau Pfeife rauchend), 1923. Etching, 9,4 x 6,9 cm. Jewish Museum Frankfurt

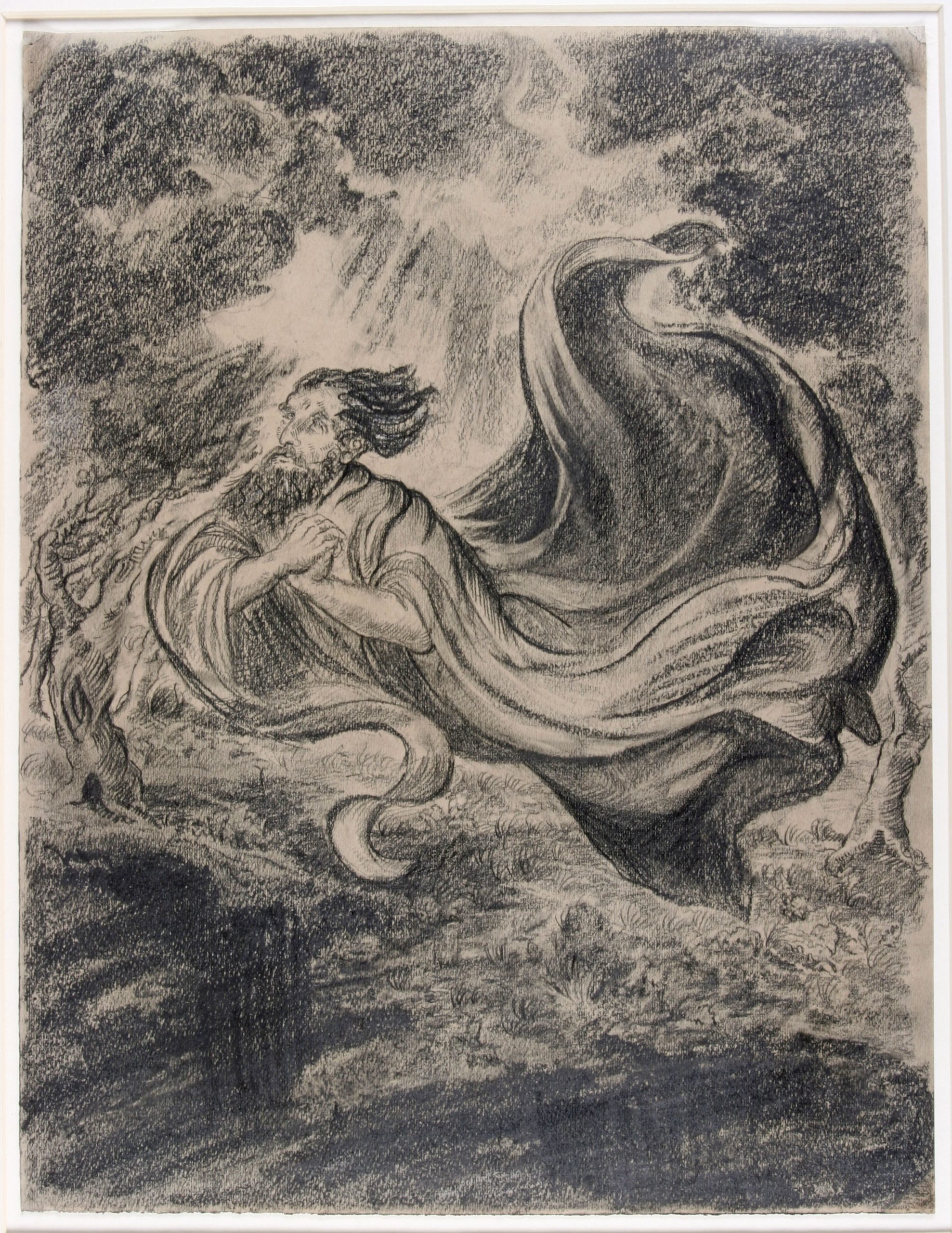

Rosy Lilienfeld, The Messiah flies over the Sambation (Der Messias überfliegt den Sambation) , 1933. Pencil and chalk on paper, 25 x 22,5 cm. Jewish Museum Frankfurt

Rosy Lilienfeld (1896, Frankfurt – 1942, Auschwitz)

Rosy Lilienfeld was born in Frankfurt am Main on 17 January 1896. The family lived in Frankfurt’s Westend district. In the early 1920s, Rosy Lilienfeld studied at the Städelschule art academy under artist Ugi Battenberg. The Städelschule also provided her with a studio in the Sachsenhausen artist’s quarter until 1936, when the contract was terminated. Unemployed from 1933, Lilienfeld could no longer pay the rent for the studio. On 17 July 1939, Rosy Lilienfeld’s mother applied for permission for herself and her daughter to emigrate to England. But rather than their journey taking them to England, it took them to Holland. From 23 November 1939, Rosy Lilienfeld was registered as resident in Rotterdam. She lived at a variety of addresses in the city until 25 February 1941. At that point, all traces of her mother are lost; her name is also not on the deportation lists. On 26 February 1941, Rosy Lilienfeld moved to Utrecht. There, she was arrested the following year and moved to the Westerbork transit camp. She was then deported to Auschwitz, where just a few weeks later she was murdered.

Some of Lilienfeld’s compositions are imbued with a strong sense of unease. Their almost nightmarish atmosphere may be an indication of the artist’s mental state. As records show, after first attempting suicide in 1923 she was diagnosed as manic depressive and was in regular psychiatric treatment until 1935.

This event is part of our monthly series Flight or Fight. stories of artists under repression.

Future events and the recordings of past events can be found HERE.

The Fritz Ascher Society is a not-for-profit 501(c)3 organization. Your donation is fully tax deductible.

YOUR SUPPORT MAKES OUR WORK POSSIBLE. THANK YOU.