Dear Friends,

Today we are all about literature.

400 years ago the poet William Shakespeare died (1564-1616). Ever since, the dramatic scenes in his plays have inspired many artists’ brush and pen, like William Turner, Edvard Munch, Max Slevogt and Lovis Corinth.

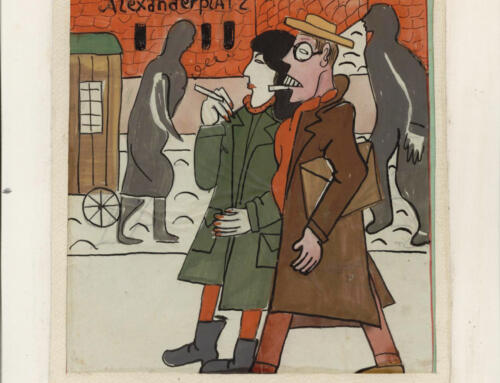

Fritz Ascher drew scenes from Shakespeare’s “King John“, “King Richard II.” and “Henry IV.” He is almost certainly inspired by numerous performances, especially in Berlin. Most famous was the Austrian theater producer Max Reinhardt, who staged Shakespeare’s plays at the “Deutsches Theater” and the “Großes Schauspielhaus”. The drawing below shows the stage in the right background; in the foreground a man and a woman sit in a box, the rest of the audience sits below. Stage plays have an important role in Ascher’s oeuvre, because they offer him the opportunity to train his skills with the actors as models. (Wiebke Hölzer, Berlin)

Congratulations, Wiebke Hölzer, for submitting the MA thesis “Religiös? Kontextualisierung der Gemälde „Golgatha“ (1915) und „Der Golem“ (1916) des Künstlers Fritz Ascher (1893-1970).” at the Humboldt University in Berlin. We can’t wait to see it published!

Not your typical summer reading, but highly recommended: This week, the ultimate book about Jewish art through the centuries came out, Ori Z. Soltes’ Tradition and Transformation. Three Millenia of Jewish Art and Architecture (Boulder, CO). This unique volume addresses the idea of Jewish art and architecture by posing and responding to a series of questions. These begin with the unresolved conceptual definition of “Jewish,” continue with the complex matter of historical definition: Abraham was called a Hebrew; Moses and David were Israelites; Ezra was a Judaean. How are these terms related to and different from the terms “Jew” and “Jewish”? Is the basis for employing “Jewish art and architecture” the work of art or the identity of the artist? If the former, is the criterion subject, style, symbol, purpose? If the latter, is it the artist’s convictions that are being labeled “Jewish”—does he or she need to be consciously trying to make “Jewish” art? Is the artist-based definition affected by birth or conversion: does an artist who converts into or out of Judaism suddenly begin to make Jewish art or cease to make Jewish art? Against the background of these questions, the narrative follows a long and wide trajectory that moves from the Israelite period to the present day, and carries from the Middle East to Europe, Asia, North Africa, South and North America as it searches for answers to these questions.https://www.amazon.com/Tradition-Transformation-Millennia-Jewish-Architecture/dp/1530201276/ref=sr_1_2?ie=UTF8&qid=1469115225&sr=8-2&keywords=soltes+jewish+art

About 1,600 artists were persecuted, ostracized and banned by the Nazi terror regime. The exhibition „‚Entartete‘ Kunst. Verfolgung der Moderne im NS-Staat“ at the Kallmann-Museum in Ismaning near Munich shows a representative selection of art by these suppressed artist, most of them are until today not known to a larger public. Gerhard Schneider has collected these works over the past 30 years to save the artists from being forgotten. The exhibition is on view until September 11. It is accompanied by an extensive catalogue edited by Gerhard Schneider and Rasmus Kleine. http://kallmann-museum.de.

Stay tuned for the opening information of the Fritz Ascher Retrospective, on September 25 at the Felix-Nussbaum-Haus in Osnabrück, Germany: http://www.osnabrueck.de/fnh/ausstellungen/vorschau/leben-ist-gluehn-der-expressionist-fritz-ascher.html

Please like us on Facebook and follow us on twitter (@Ascher_Society)!

Have a wonderful summer,

Rachel Stern

Director and CEO