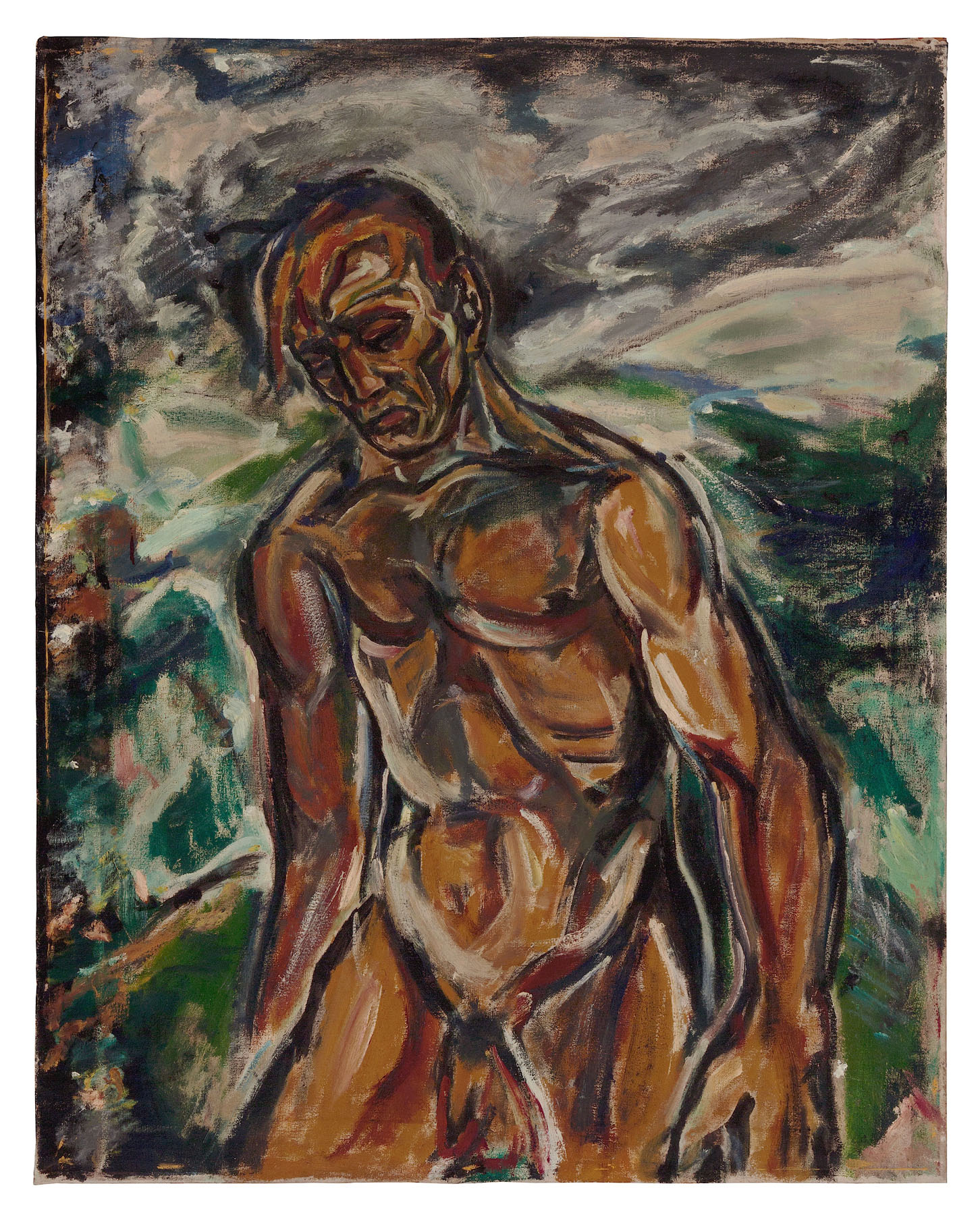

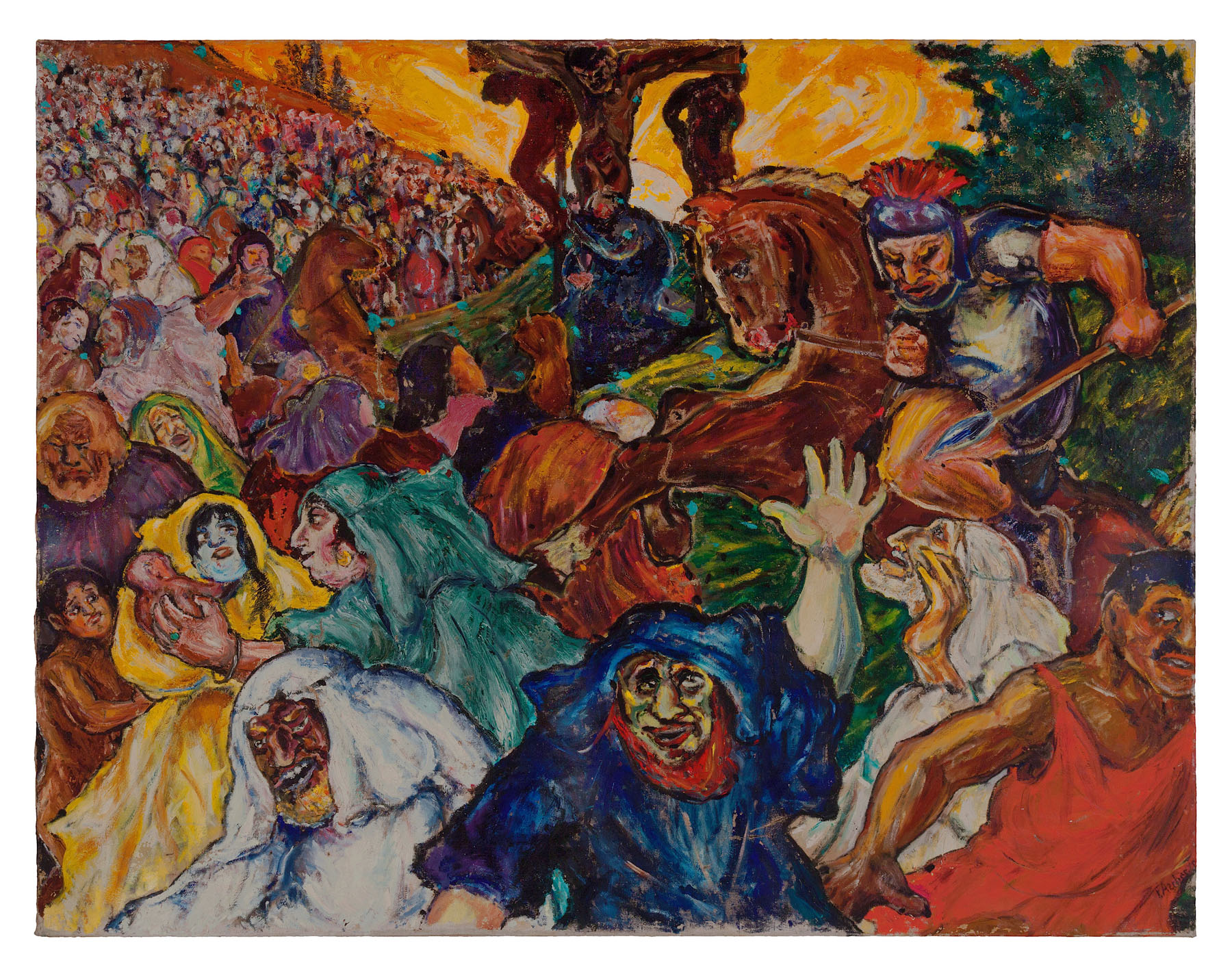

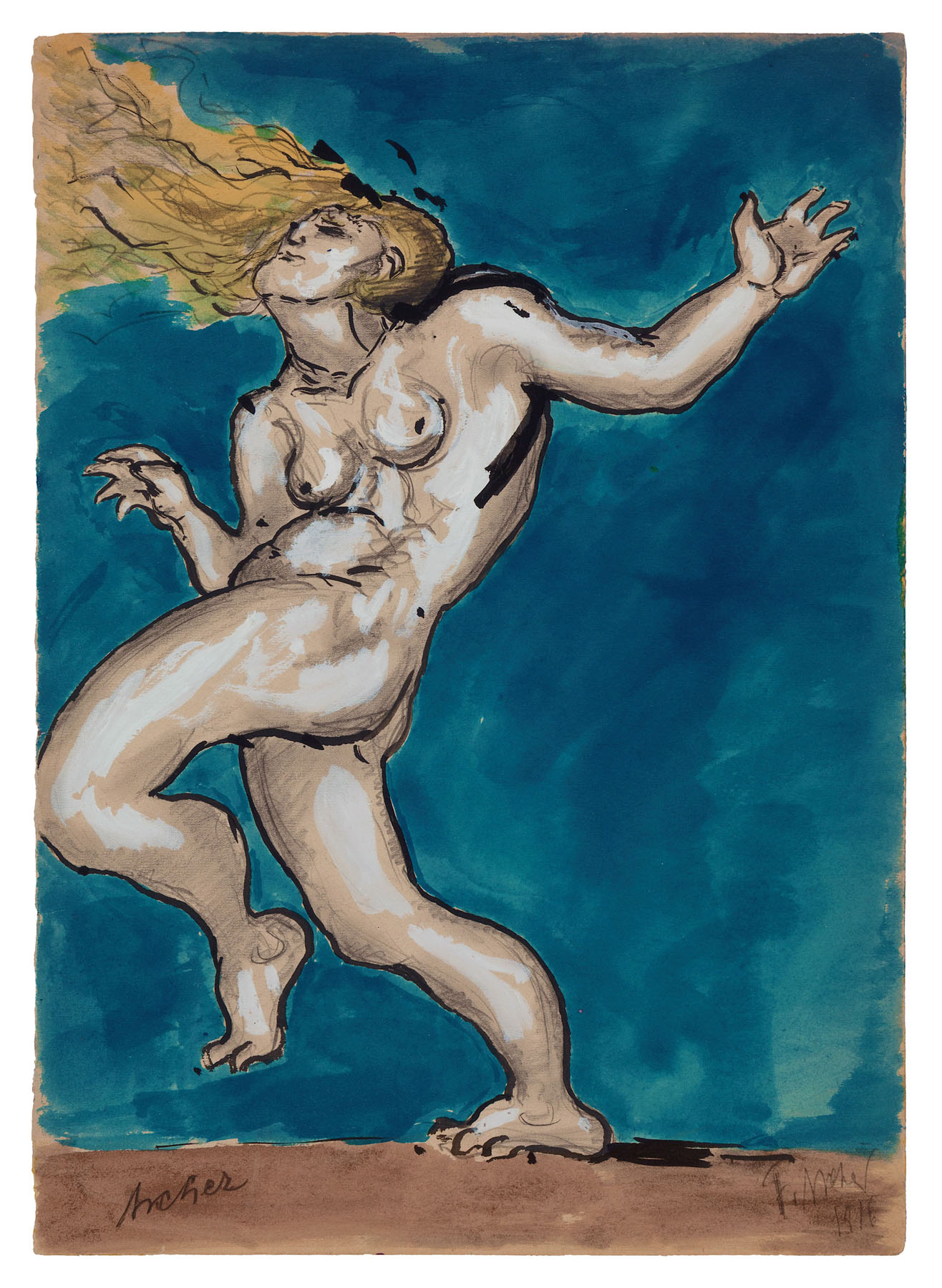

Fritz Ascher (17 October 1893 – 26 March 1970 in Berlin, Germany) was a German artist, whose work is characterized by Expressionist and Symbolist sensitivity. In paintings, works on paper and poetry he explored existential questions and themes of contemporary social and cultural relevance, of spirituality and mythology. Ascher’s expressive strokes and intense colors create emotionally intense and authentic work.

Re-discovered in 2016, with an international retrospective and a scholarly publication, Fritz Ascher’s strong and unique artistic voice has taken its rightful place in German Expressionism.

1893-1913

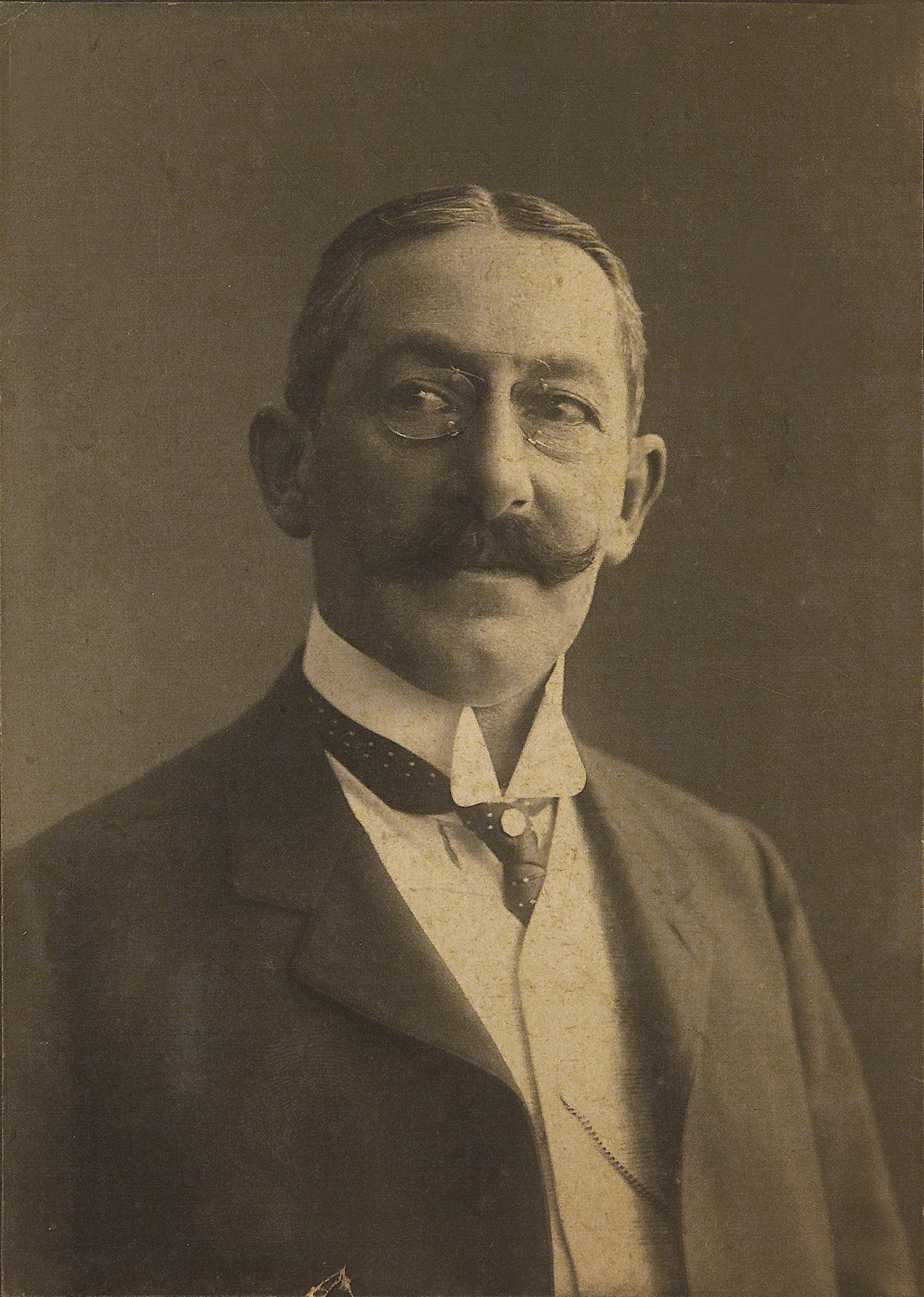

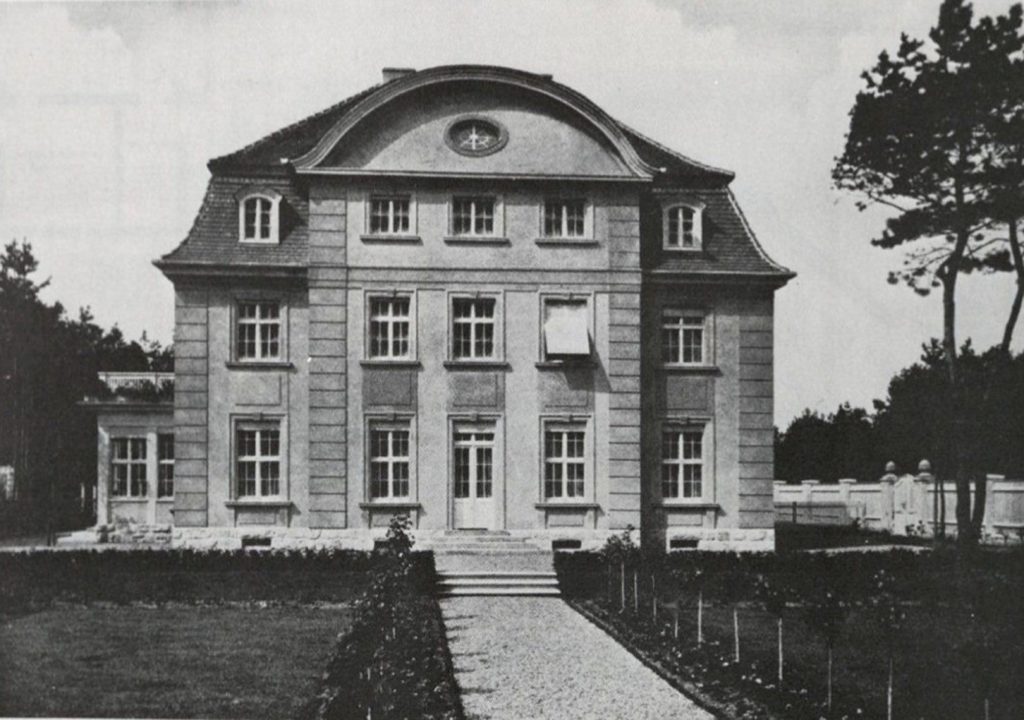

Fritz Ascher was born in Berlin, on October 17, 1893, the son of the dental surgeon and businessman Dr. Hugo Ascher (born Neugard July 27, 1859 – died August 18, 1922 Berlin) and Minna Luise Ascher (born Schneider; Berlin, January 17, 1867 – died October 17, 1938). His sisters Charlotte Hedwig and Margarete Lilly (Grete) were born October 8, 1894 and June 11, 1897. Hugo Ascher converted his three children to Protestantism in 1901, his wife remains Jewish. Hugo Ascher’s business was successful, and in 1909 the family moves into a villa in Niklasstraße 21-23 in Berlin-Zehlendorf, built by the prominent architect Professor Paul Schultze-Naumburg.

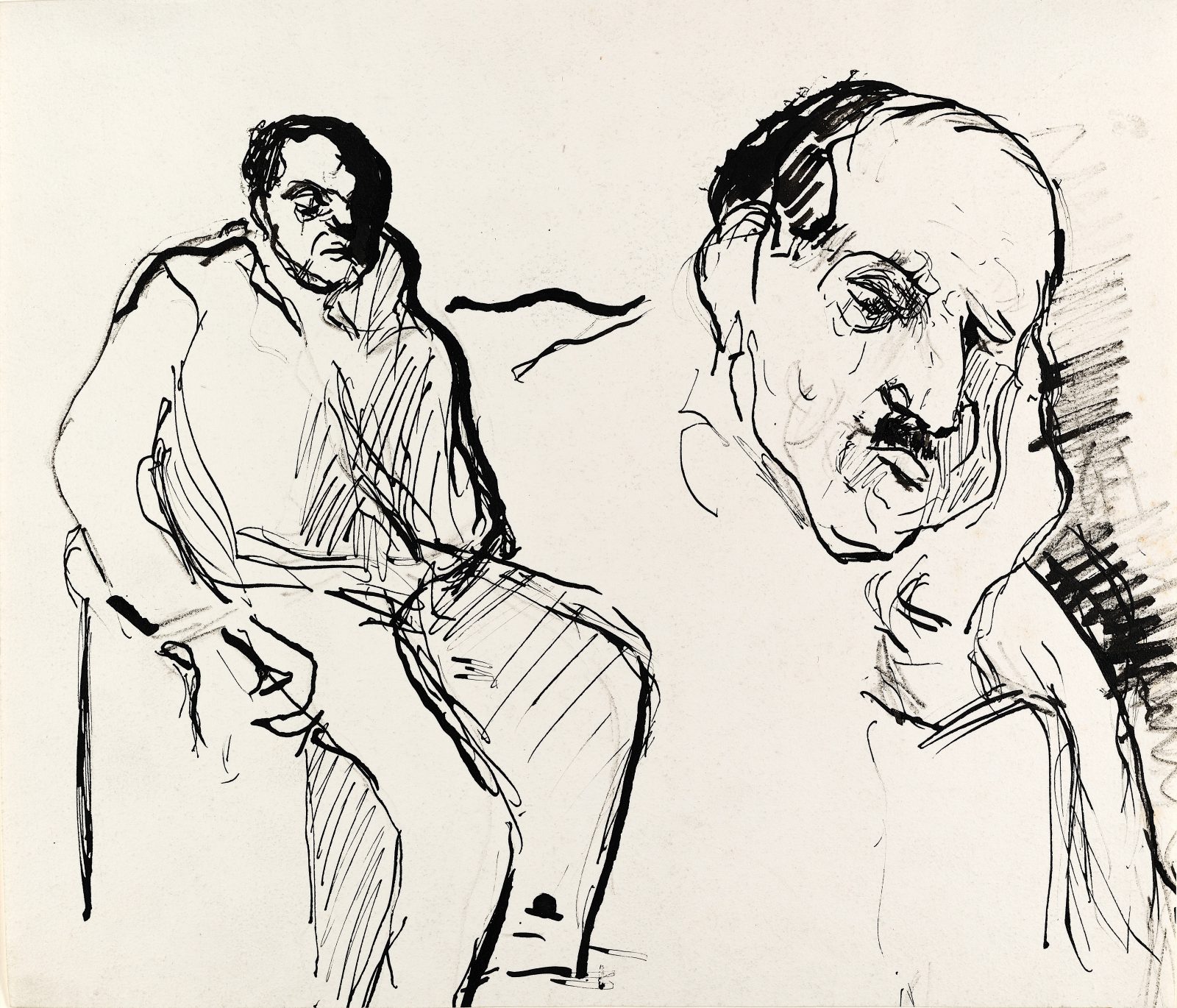

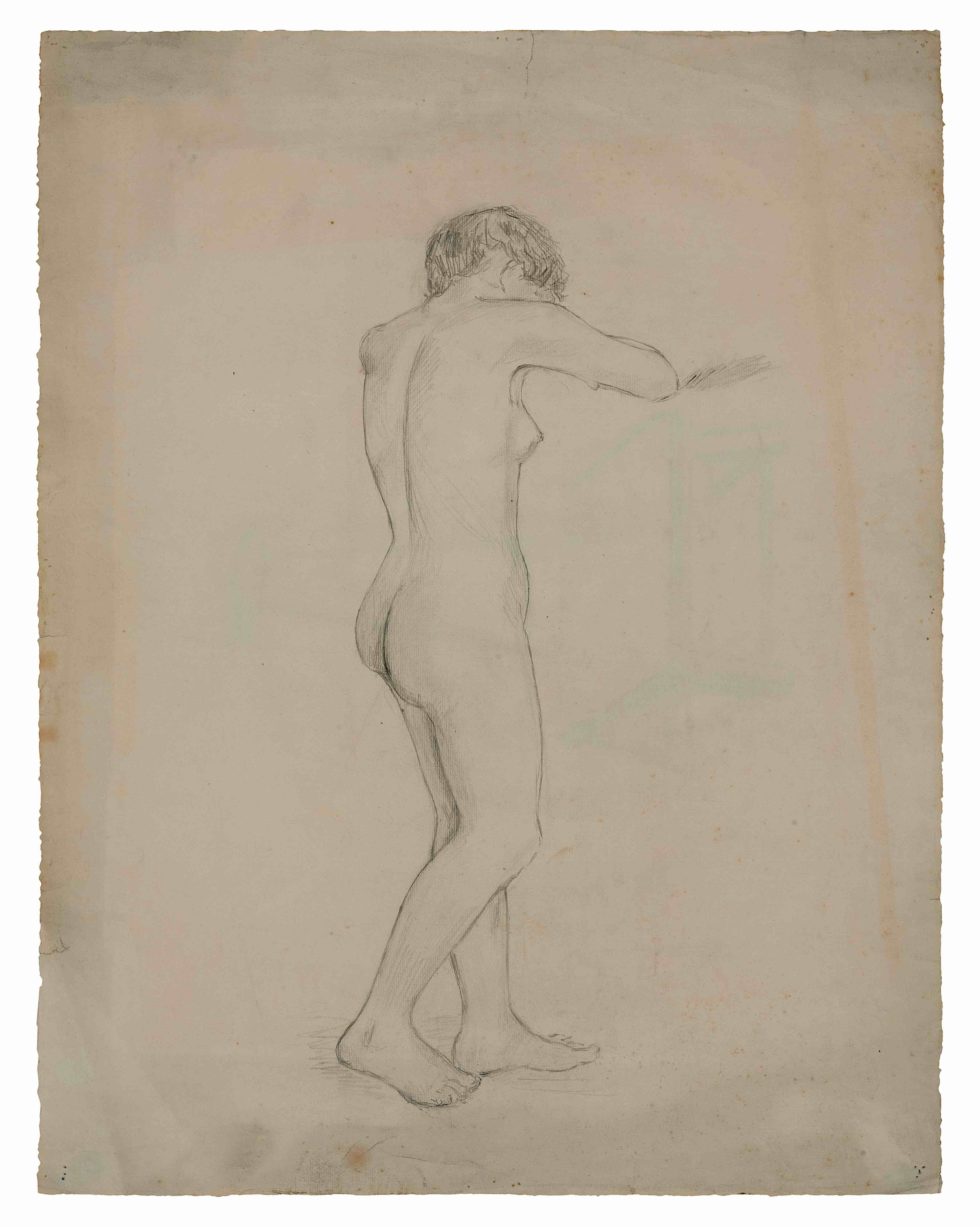

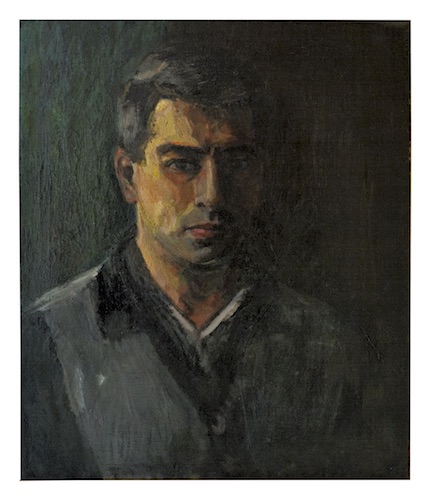

Recommended by Max Liebermann, Fritz Ascher studied at the Art Academy Königsberg, where it’s dean Ludwig Dettmann, co-founder of the Berlin Secession, had hired dynamic teachers who emphasized the value of a solid, practical education. Among others, the artist befriended Eduard Bischoff, who painted a portrait of him in 1912. In Berlin, Ascher studied with Lovis Corinth, Adolf Meier, and Kurt Agthe.

1913-1933

Ascher was active in the networks of the Berlin avant-garde, and knew many artists personally. Influenced by Expressionist artists such as the older Edvard Munch, Emil Nolde and Wassily Kandinsky, and his contemporaries Max Beckmann, Georges Rouault and Ludwig Meidner, Ascher found his very own artistic language.

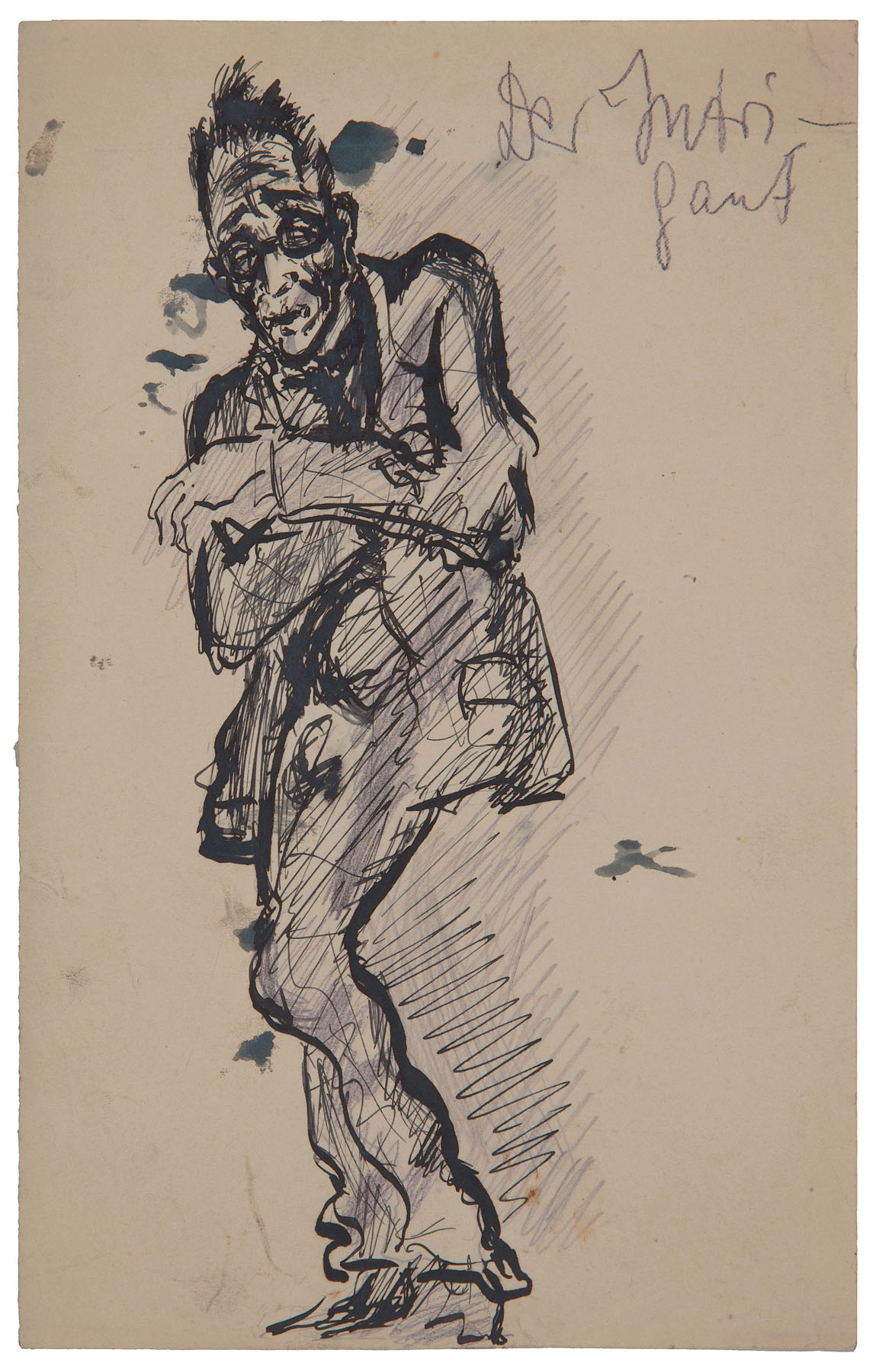

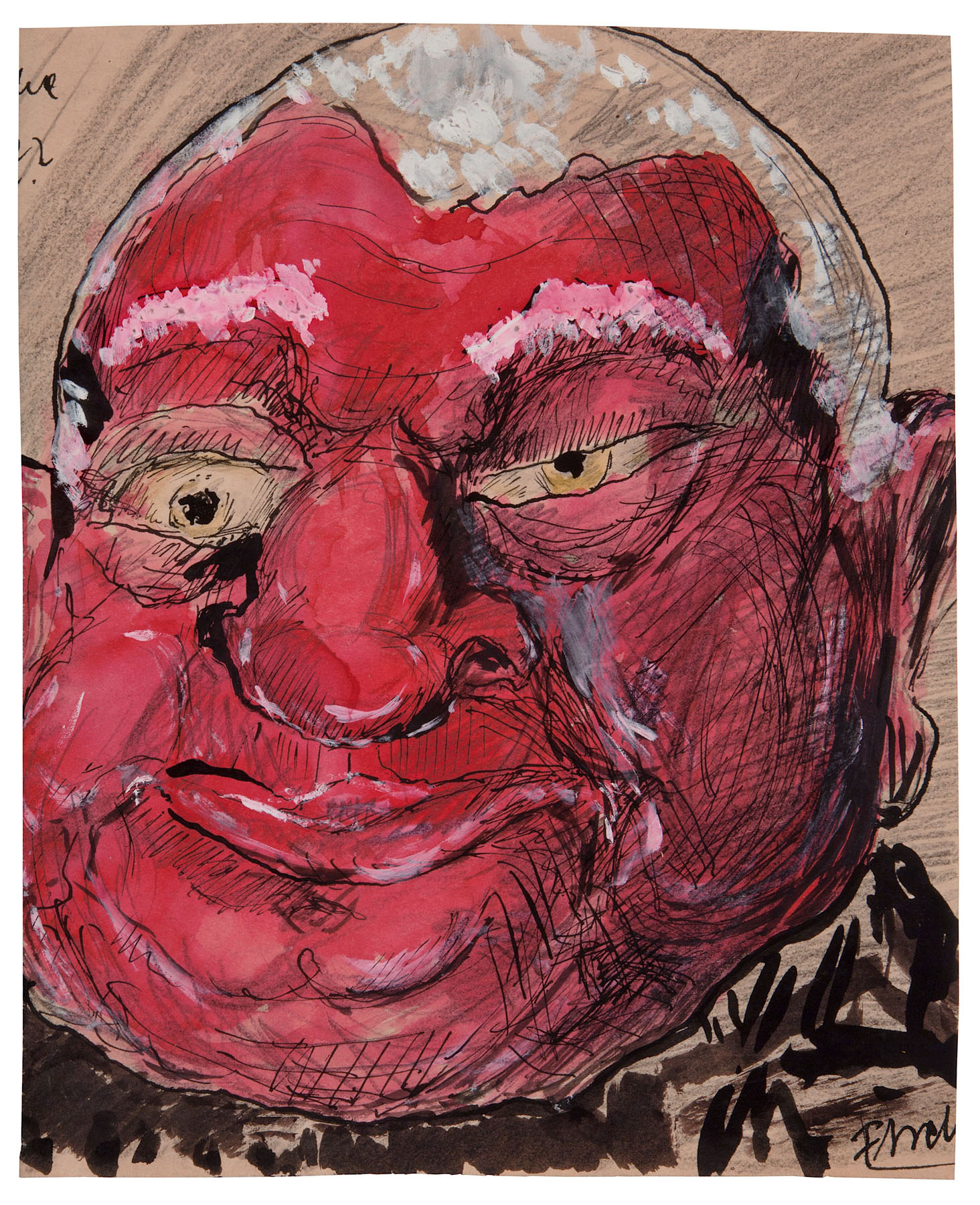

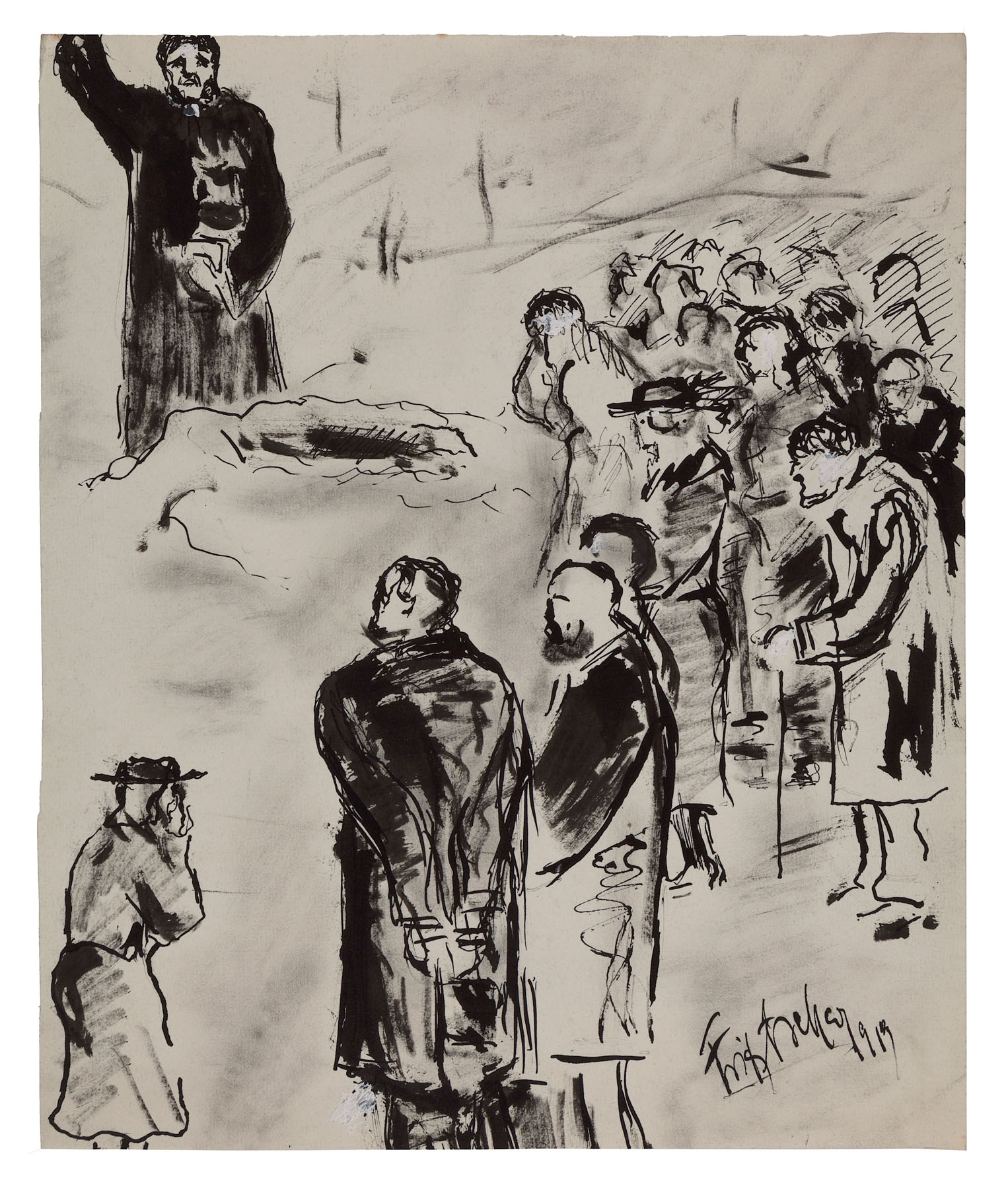

He traveled extensively and started exhibiting his work. In 1914, Ascher and his friend and fellow painter Franz Domscheit (Pranas Domšaitis) presumably traveled to Norway and met Eduard Munch in Oslo. In 1918–19, the two friends stayed in Bavaria. Here, Ascher befriended the artists the Blue Rider and the weekly Simplicissmus, among them Gustav Meyrink, Alfred Kubin, George Grosz and Käthe Kollwitz, and sent his paintings to various exhibitions and galleries, including the Glaspalast.

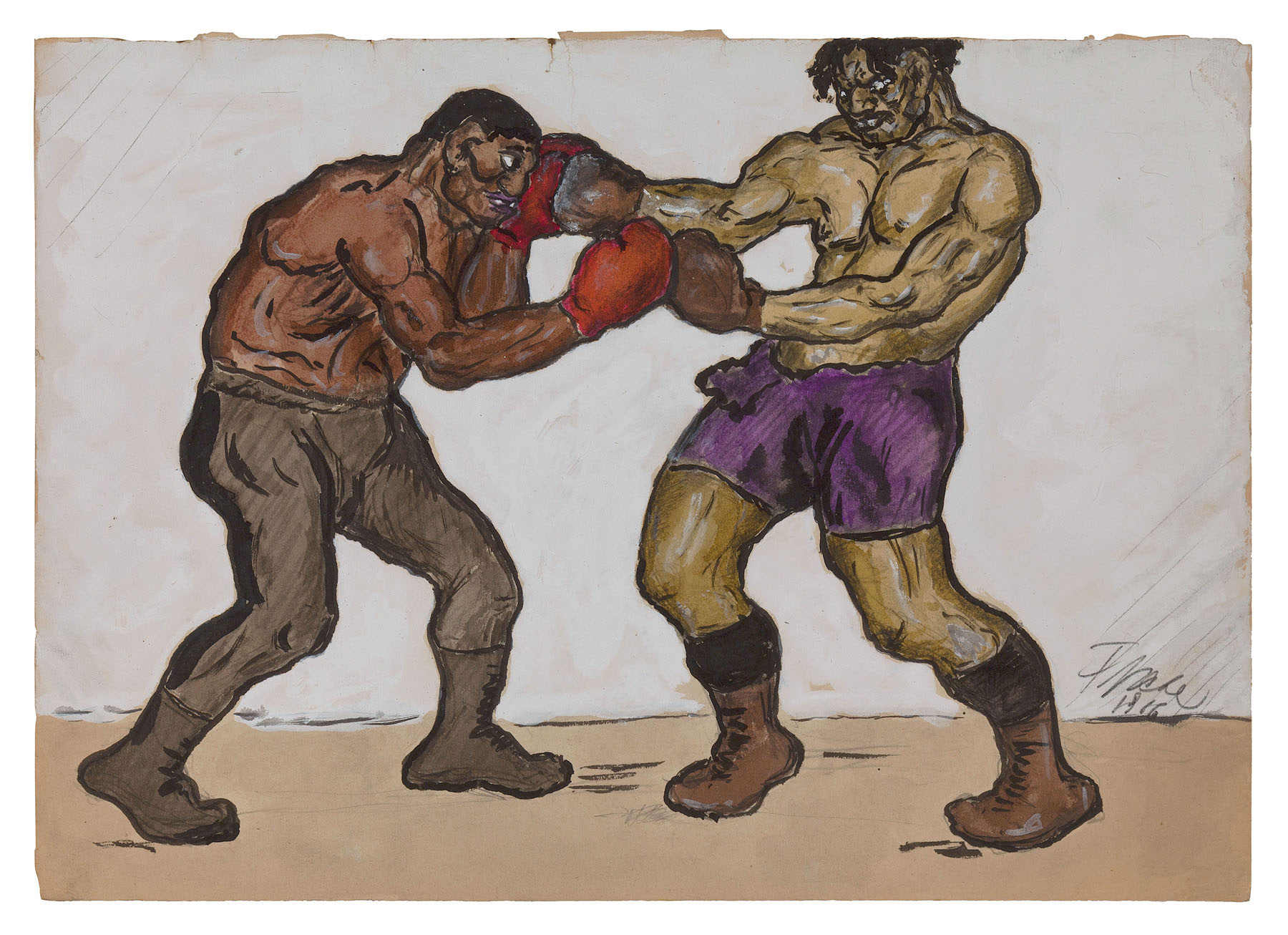

Ascher’s expressive strokes and intense colors with descriptive outlines and areal color combine elements of Expressionism with those of Symbolism. His early work is very multifaceted in themes, the techniques used and the style of painting. The result is a fascinating field of tension between small intimate graphite drawings and large-format polychrome figural compositions, between portraits and biblical scenes, character and milieu studies or between representations of literary and allegorical figures. At the same time, he responded to contemporary themes, such as the street fights of the November Revolution of 1918.

1933-1945

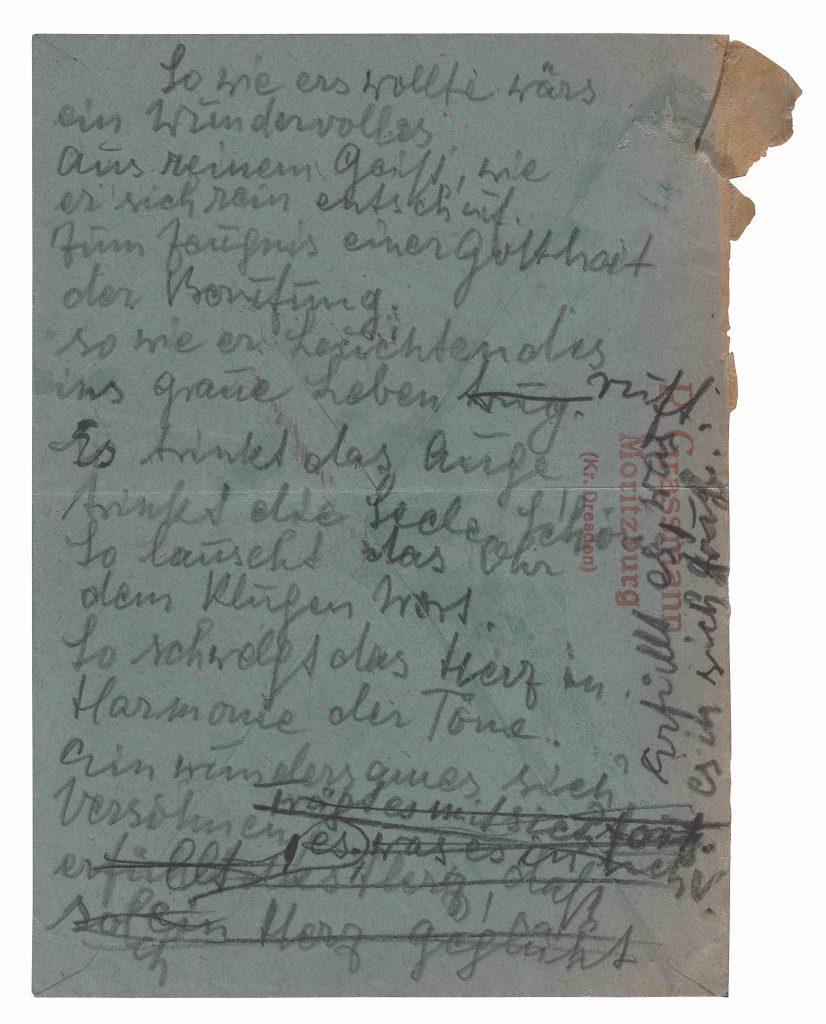

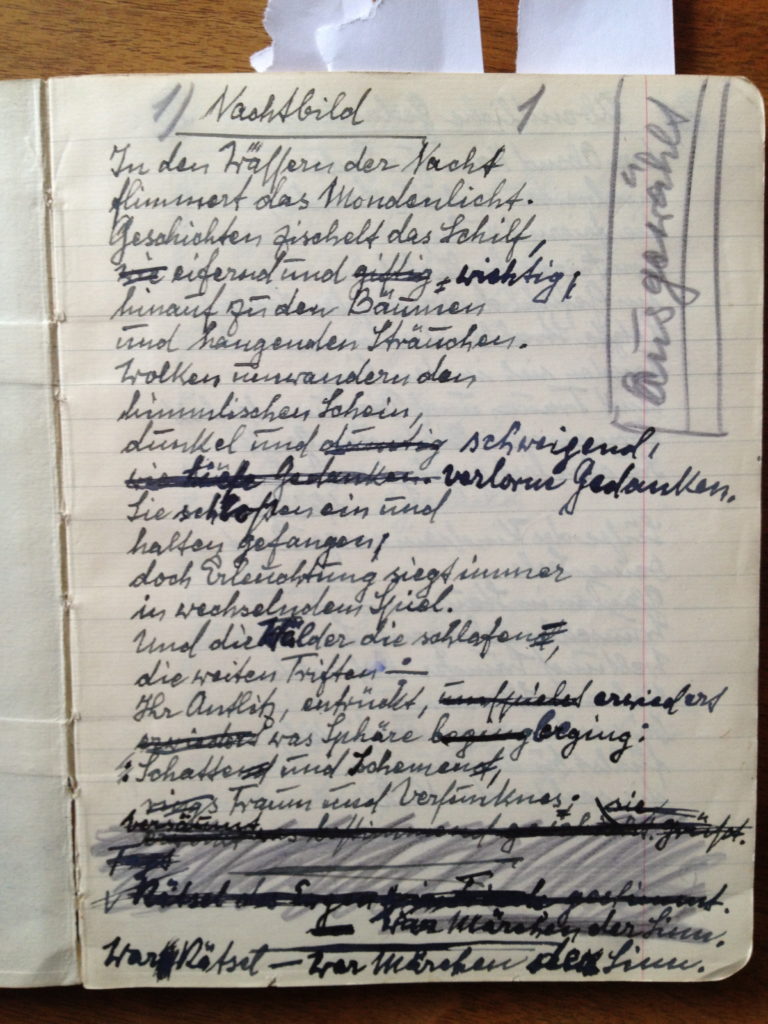

On January 30, 1933 Hitler assumed power. As Modern painter and Jewish-born, Ascher could no longer produce, exhibit, or sell his art. He hid among friends in Berlin and Potsdam, constantly changing his residence. During the Pogroms on November 9-10, 1938, Ascher was arrested and interned in the concentration camp Sachsenhausen and in Potsdam Gestapo prison. Released six months later, he survived the Nazi terror regime hiding in a cellar of a partially bombed-out building in the wealthy Grunewald neighborhood in Berlin. During this time he wrote poems about love and the divine, and tributes to his artistic role models. In other poems, he turned to a new theme: they evoke nature as a place of refuge and a spiritual home. These poems give a glimpse into the artist’s innermost feelings and can be understood as “unpainted paintings.”

1945-1970

After Hitler’s defeat, Ascher continued to live in Berlin Grunewald. Withdrawn from society, he threw himself into his work.

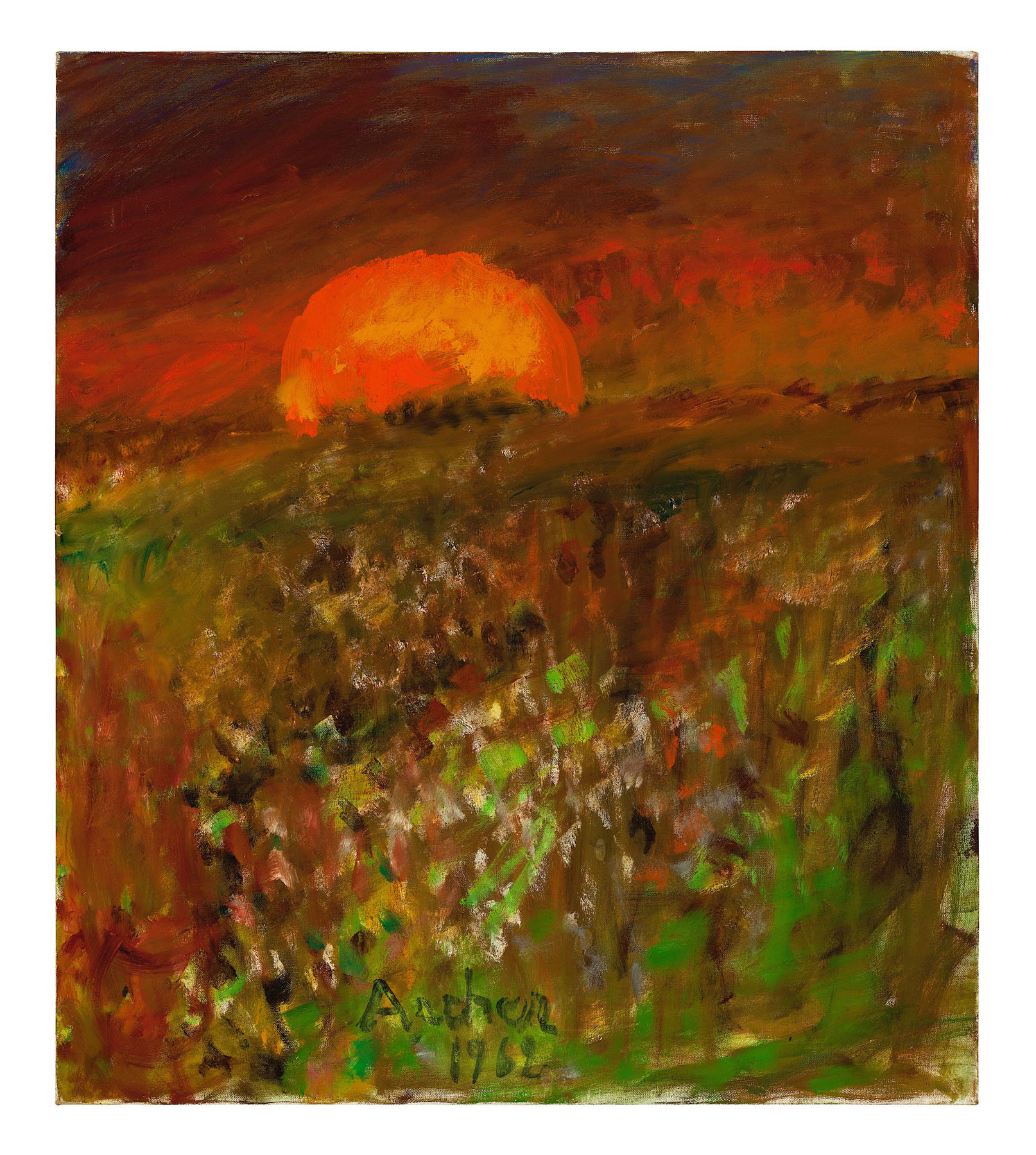

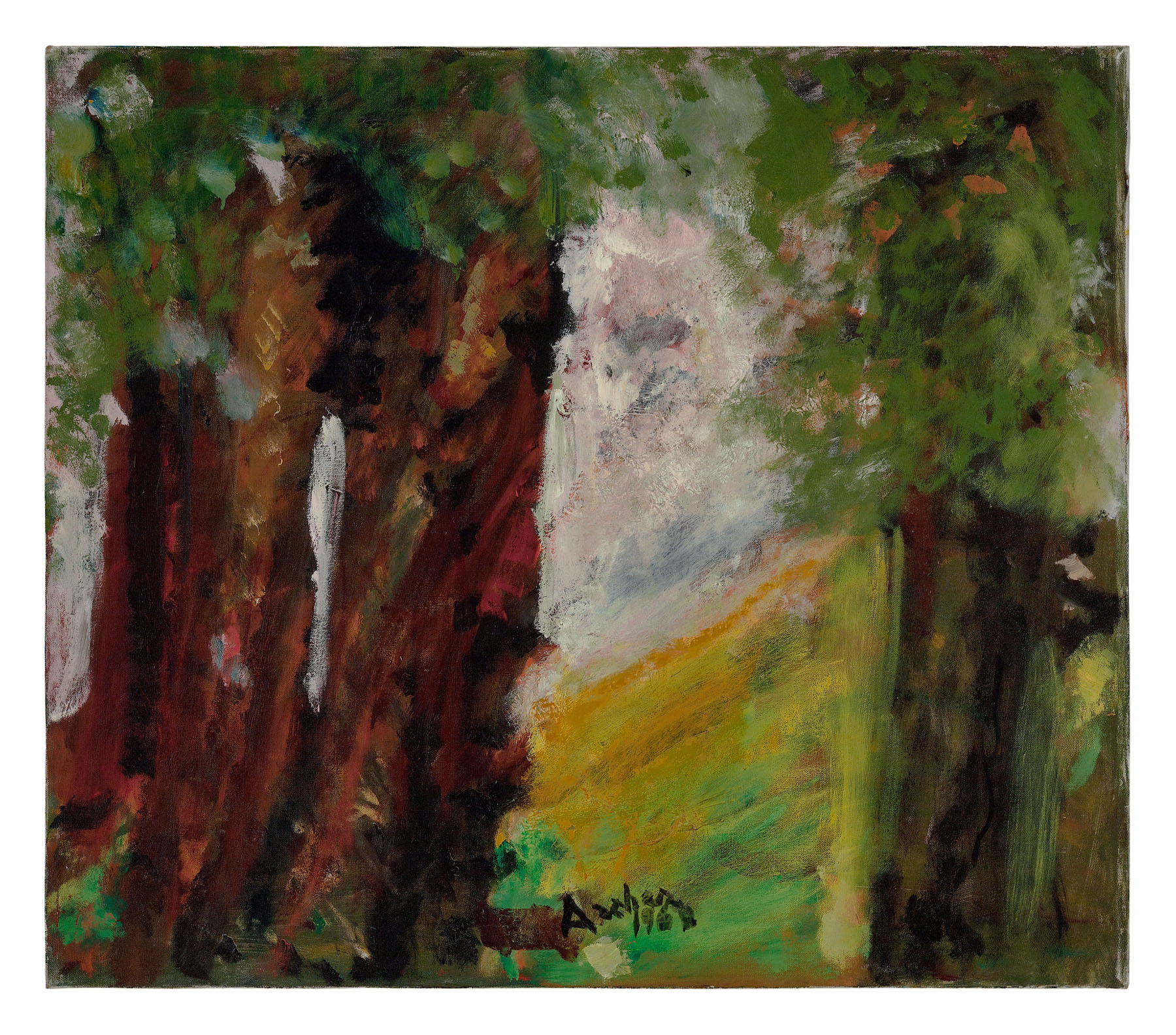

Initially he painted over some of his early work, but soon he focused mainly on landscapes, only sometimes drawing people from memory. Ascher worked with renewed immediacy and urgency, dramatically simplifying forms and medium. His thick, bright pigments suggest both vibrant, life-affirming joy and, in the rough-hewn nature of his brushstrokes, a dark, inner anguish transformed into light. The emotional narratives of his early work were replaced by economical landscape images and stylized flowers and trees, single-mindedly repeated at an intimate scale. Near-obsession combined with close observation and an appreciation of nuance. Especially the trees, singly or in rows, in groups of two or three, became standing figures that confront us, each as unmistakable as each individual. (Karen Wilkin)

Fritz Ascher died in 1970, only months after a large solo exhibition at the legendary Rudolf Springer gallery in Berlin.