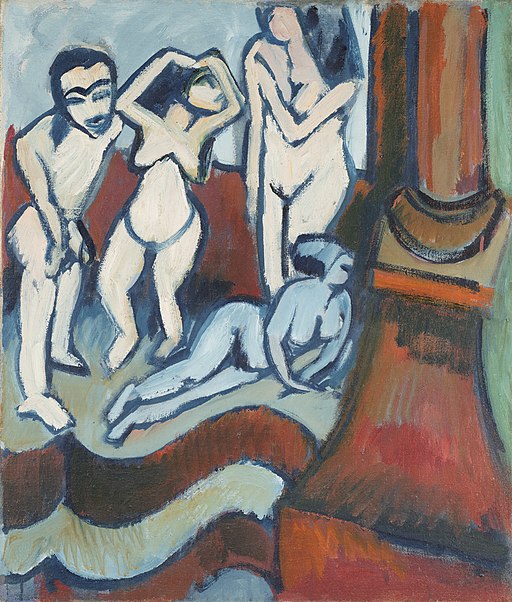

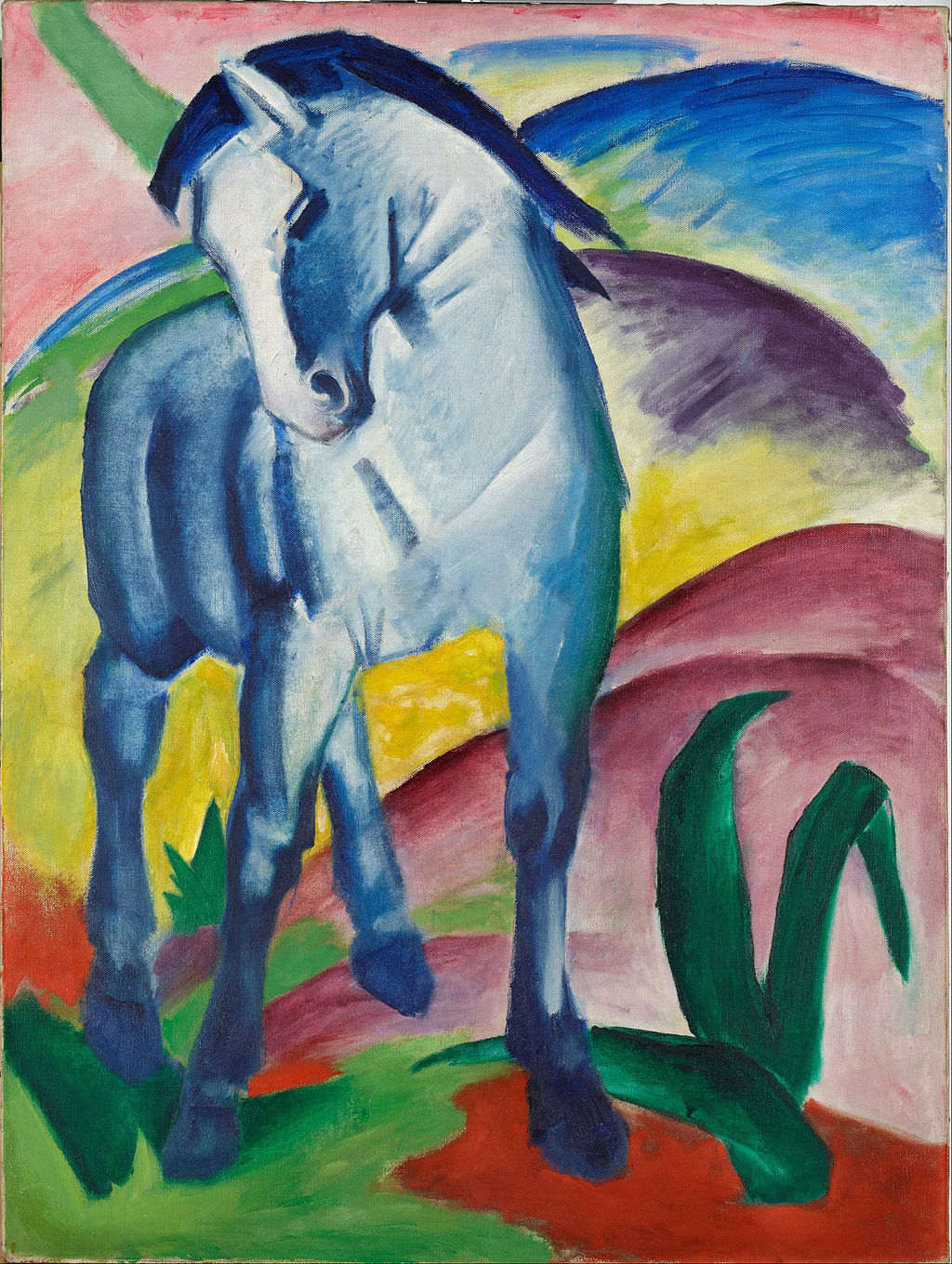

“Expressionism” in art history is a term with a complicated and often retrospective history. Today, when we speak about “German Expressionism”, we often refer to the work of two groups prior to the First World War: Die Brücke and Der Blaue Reiter. However, the connection between these two collectives of artists was retroactively applied—indeed, one of the first times the two groups were linked together as “German Expressionists” was when they were hung together in 1937 at the infamous Nazi Degenerate Art Exhibition. In its initial uses, “Expressionism,” for instance, was defined in 1908 by Wilhelm Worringer in his dissertation Abstraction and Empathy as part of a dichotomous drive towards what he viewed as “abstraction”, formed by “primitive” desires. “Expressionism” as a category would later encompass a variety of styles that today we think of as discrete categories of art practice, including work by artists we consider Cubists. However, despite the fluidity of the term in its historical uses, there are characteristics of what we think of as “Expressionism” today and in Ascher’s time that resonate with his body of work.

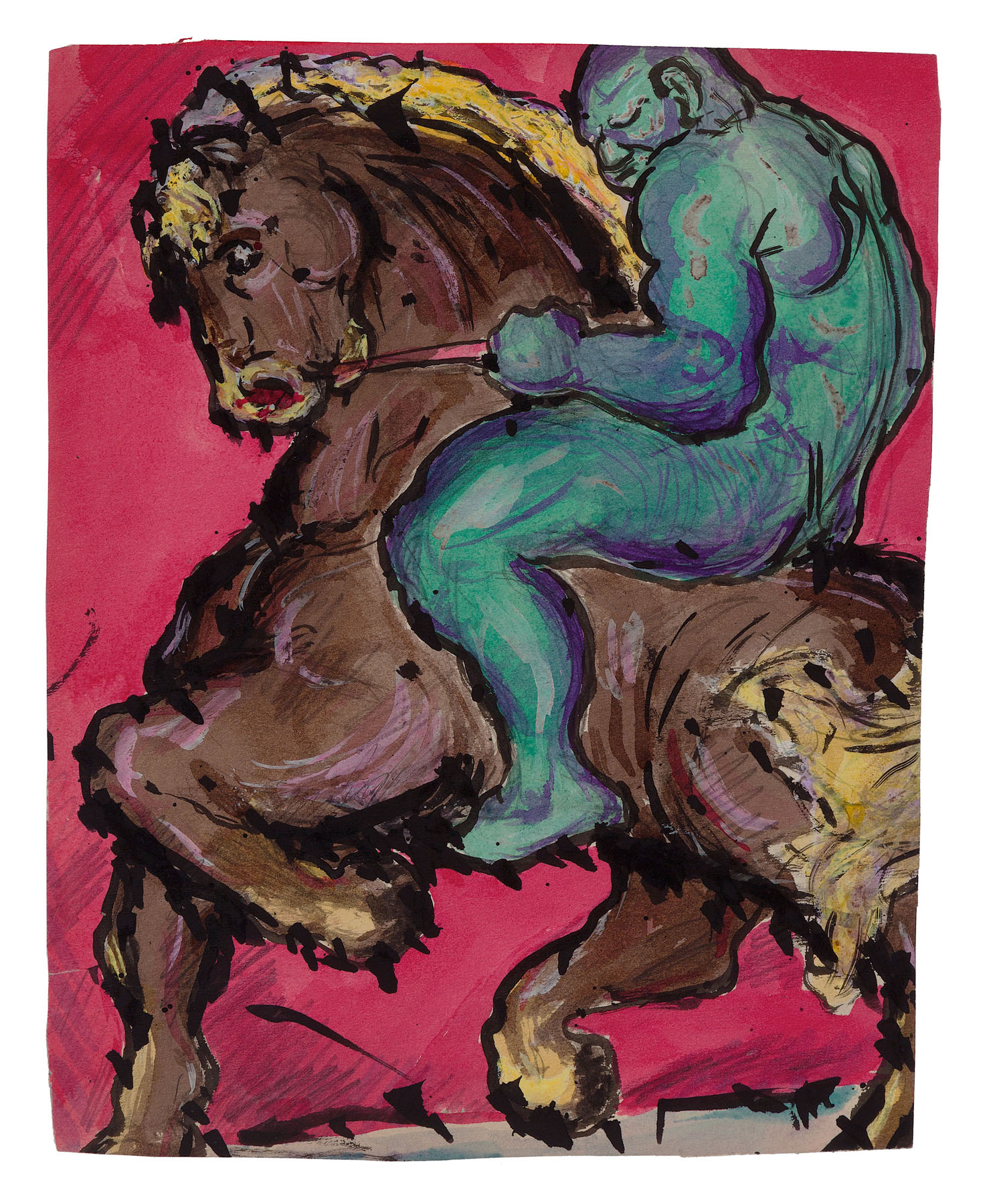

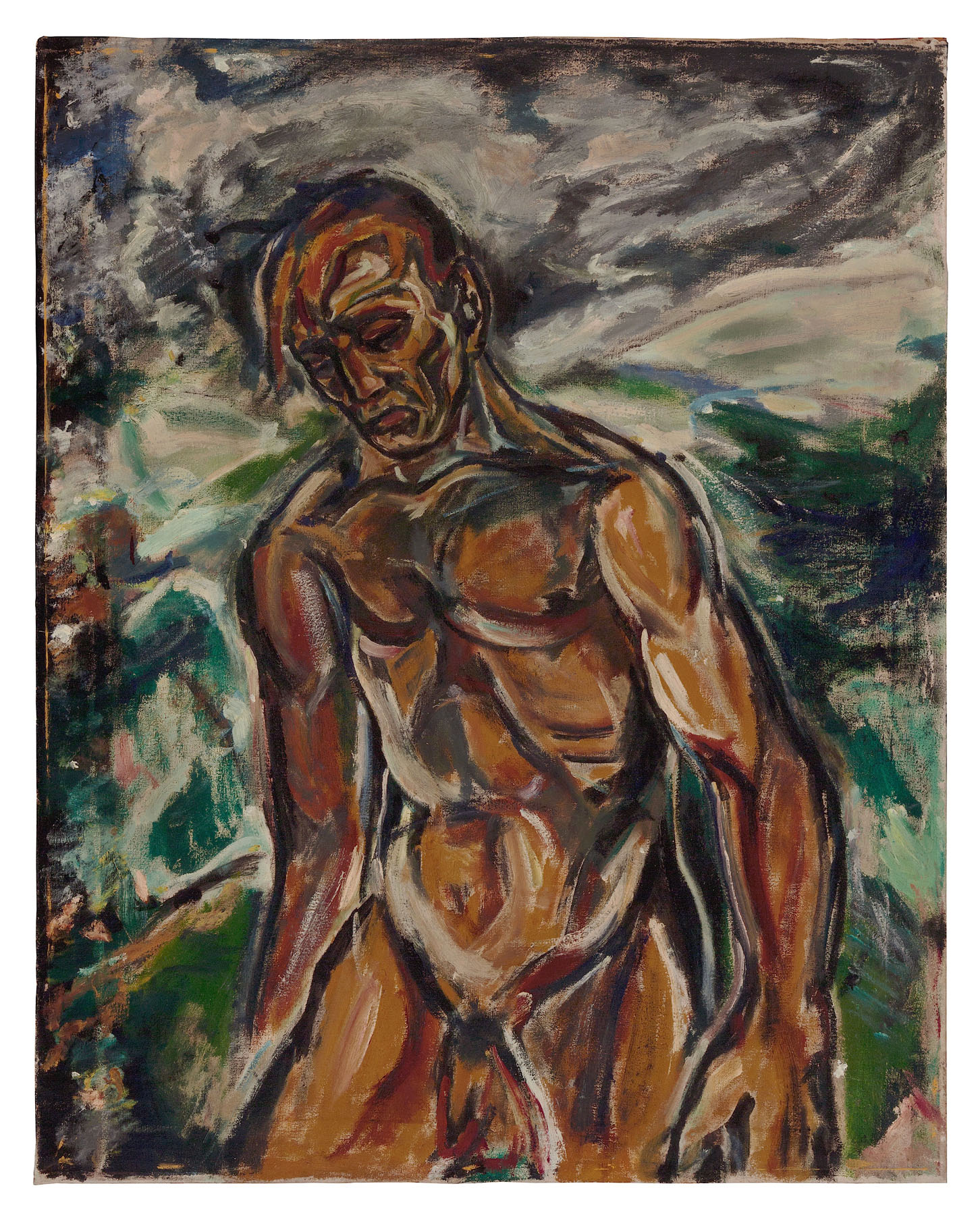

“Expressionism” brings to mind freedom, a concern with the conveyance of inner life rather than following outward models of visual perfection and order. We think of a fluidity of brushstroke, a concern with gesture, a particular type of non-naturalism in which the world is manifested on canvas or paper as a statement of the artist’s immediate feeling, or of the essence of a subject rather than a mimetic, physical copy. “Expressionism” conjures up images of vibrant non-naturalistic color, and a hybrid of sources of inspiration, deriving from Western as well as non-Western models.

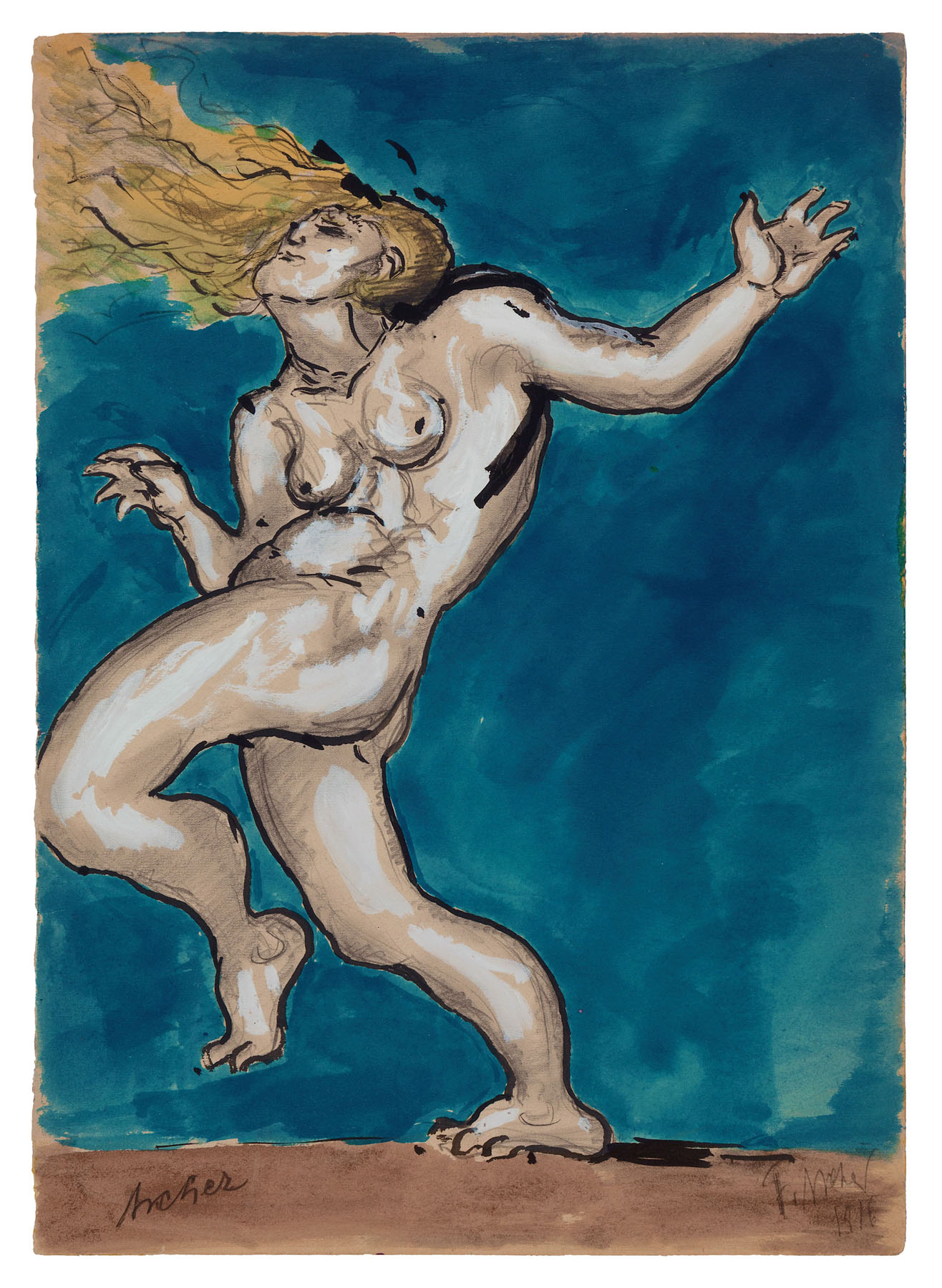

For Ascher, the category of “Expressionism” is essential to understand his practice. On the one hand, Ascher was close and associated with several artists who today we think of as “Expressionists,” including members of Die Brücke. On the other hand, the evocative gestures, dramatic color juxtapositions, non-naturalistic figurations with aspects exaggerated for emotional effect, as well as an Expressionist concern with depicting states of experience beyond the visual—i.e., music—all align Ascher’s compositional practice to those artists whom we today consider the German Expressionists, and to those artists of the later 20th century, such as the Abstract Expressionists, who equally focused on the affective potential of gestural line.

DigiFAS Quick Clips

Interview with Rose-Carol Washton Long, September 17, 2020

“What is Expressionism?”

Elizabeth Berkowitz interviews Rose-Carol Washton Long, Professor Emerita of Art History at the Graduate Center, City University of New York, about “Expressionism” in all of its forms and definitions. Broadly arranged to answer the question “What is Expressionism?” the interview addresses the origin of the term “Expressionism” in art history, the historical movements we think of as “Expressionist,” the connection between German nationalism/internationalism and “Expressionism,” and the distinction between “expressionism” (little “e”) and “Expressionism” (capital “E”) in art historiography. The conversation discusses the degree to which we should consider Fritz Ascher a German Expressionist artist, as well as the legacy of Expressionist practice in the post-World War II era.

Ascher and German Expressionist Peers

Explore Further

All Fritz Ascher Images © Bianca Stock.